AUGUSTUS: What a gift you Greeks have. Incidentally, the battle, you know: it wasn’t like that. No, not at all. But you described it poetically, I understand that. It was poetic licence. I’m used to that.

— I, Claudius, Episode 1, “A Touch of Murder”

Watching I, Claudius for the first time recently was a surprising experience.

It wasn’t surprising because it was great. Of course it was great. Of course it was one of the greatest television shows ever made. I’d been told that for years, I just had to get round to watching it. No, the surprise was in how damn funny it was, an aspect of the show I had somehow managed to avoid being informed about. Which I guess is fairly ignorant regardless; even iPlayer describes it as an “acclaimed blackly comic historical drama series”.

LIVIA: These games are being degraded by the increasing use of professional tricks to stay alive, and I won’t have it. So put on a good show, and there will be plenty of money for the living and a decent burial for the dead.

Brilliant though the show is, initial reviews of the series were predictably mixed. And one review in particular has become somewhat notorious. I first became aware of it from Wikipedia:

“The initial reception of the show in the UK was negative, with The Guardian commenting sarcastically in its first review that ‘there should be a society for the prevention of cruelty to actors.'”

This isn’t just an unsourced piece of Wikipedia nonsense; the citation seems reasonable enough. It comes from a November 2012 article in The New York Times, “Imperial Rome Writ Large and Perverse”:

“But looking back wryly weeks ago on the original production, [director] Mr. Wise recalled that it did not seem destined for greatness. In Britain, The Guardian review of “I Claudius,” he said, began, ‘There should be a society for the prevention of cruelty to actors.'”

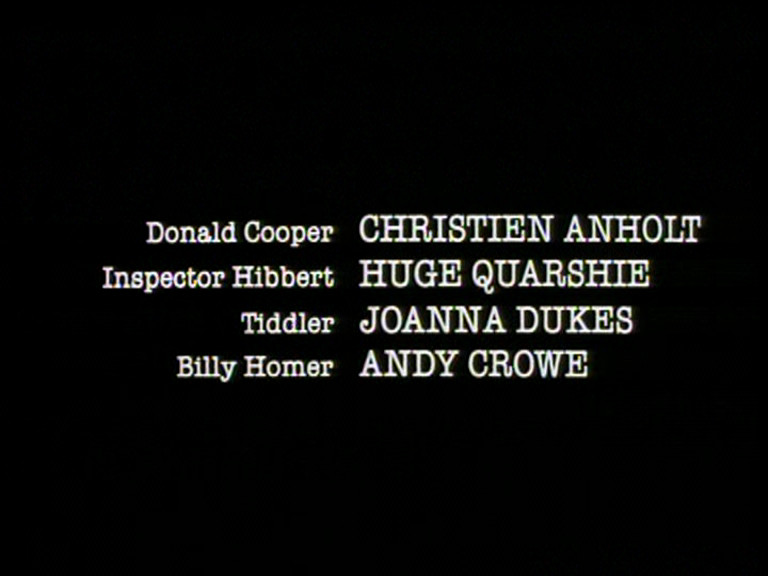

That article thankfully gives the source for all of its quotes from Herbert Wise: “a documentary that accompanies the 35th-anniversary I, Claudius DVD set”. It isn’t too difficult to work out exactly which documentary: it’s I, Claudius: A Television Epic, which was made for the 2002 DVD release of the series.

Certainly The New York Times is quoting Wise more-or-less correctly; here’s what he says in that documentary verbatim:

HERBERT WISE: I remember The Guardian critic – whose name I remember but I won’t quote it now – starting his criticism by saying: “There ought to be a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Actors.”

This single quote is responsible for all the repeated anecdotes surrounding our supposed Guardian review. The New York Times article itself is syndicated everywhere for a start, but it’s spread well beyond that. For instance, in April 2022, The New European ran a piece called “The show that started a TV toga party”:1

“The show was a modest ratings hit for BBC2 (averaging an audience of around 2.5 million an episode), but reviews were initially dismissive, with The Guardian snottily proclaiming: “There should be a society for the prevention of cruelty to actors.” But I, Claudius was soon re-evaluated and won greater popularity with repeat transmissions, as well as three Baftas.”

The line has also started to make into books; Arthur J. Pomeroy’s A Companion to Ancient Greece and Rome on Screen (Wiley, 2017) directly quotes Wise:

“Herbert Wise remembered the Guardian critic “starting his criticism by saying ‘There ought to be a society for the prevention of cruelty to actors'” (I, Claudius: A Television Epic, 2002).”

And coming right up to date, in August 2023 the Socialist Worker published the article “Roman history made into classic TV viewing”:

“Initially critics tore it apart. “It was so badly received in its first two weeks,” recalled Sian Phillips, who played Livia, “because it was so different.” The Guardian – which now says it is a masterpiece – loftily proclaimed, ‘There should be a society for the prevention of cruelty to actors.'”

Here’s the problem: The Guardian said nothing of the damn sort.

Though the URL seems to indicate it was originally called “How I, Claudius Kickstarted Game of Thrones”. The original headline is better. ↩