Part One • Part Two • Part Three • Part Four • Part Five

Content warning: very mild nudity.

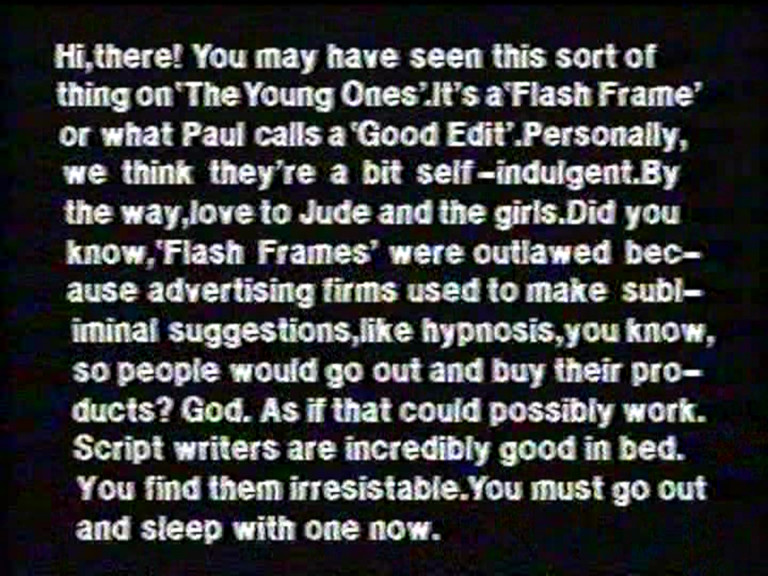

When we last left Spitting Image, the team had just got themselves into a spot of bother. On the 10th June 1984, the show broadcast the following message, for one single frame:

Our old friend Tooth and Claw reveals the immediate fallout:

“It was not many hours before a viewer with a freeze-frame facility brought it to the attention of the IBA. Stephen Murphy, the IBA programme officer who had been so indulgent with Spitting Image in the early days, called up John Lloyd with a new tone of voice: ‘My dear boy, you’ve broken the law. Haven’t you read the Broadcasting Act?’ Lloyd confessed that he hadn’t but said he had read the offending text over to Central’s duty lawyer who had cleared it and had, in any case, thought the prohibition related specifically to advertising. Murphy, apparently unimpressed, hung up with: ‘You’ll be hearing from me at some future date.'”

When we discussed Labour’s Party Political Broadcast from 1970 and Ross McWhirter, we spent a lot of time with the ITA and the Television Act 1964. By the time we get to Spitting Image, the ITA has become the IBA, and the Television Act 1964 has been replaced with the Broadcasting Act 1981.1

The relevant section of the new Broadcasting Act is 4(3):

“It shall be the duty of the Authority to satisfy themselves that the programmes broadcast by the Authority do not include, whether in an advertisement or otherwise, any technical device which, by using images of very brief duration or by any other means, exploits the possibility of conveying a message to, or otherwise influencing the minds of, members of an audience without their being aware, or fully aware, of what has been done.”

You will note that this is word-for-word identical to section 3(3) of the Television Act 1964. You will also note that Lloyd’s impression that “the prohibition related specifically to advertising” is most definitely wrong; subliminal material is clearly stated to be banned “whether in an advertisement or otherwise”.

Tooth and Claw continues:

“On this wording, it looked as if anyone who cared to bring a prosecution would have the IBA bang to rights. On the day after the incident, the IBA sternly reprimanded Central as the responsible company and Central told Lloyd never to do such a thing again, making it an area to which he would irresistibly return.

It was the quality of naughtiness, rather than politically-motivated satire, that was now becoming Spitting Image‘s defining characteristic.”

In fact, nobody did care to bring a prosecution for the above incident. But Tooth and Claw does state that somebody had “complained to the IBA’s director-general, John Whitney, in the strongest terms”.

Who was that somebody? None other than a certain Norris McWhirter. This fact is not only mentioned in Tooth and Claw, but also evidenced by letters in the IBA archive. Ross McWhirter was murdered by the IRA in 1975; his brother Norris had clearly taken up Ross’s crusade against subliminal messages, whether in good faith or otherwise.

But for now, there is where things ended. There were no mentions of the incident in the last episode of the series on the 17th June, though the temptation must surely have been strong.2 And after that, not even Spitting Image could cause trouble while they were off-air. Central and the IBA would get six months respite from all this nonsense, at least.

* * *

Spitting Image returned to the screen at the end of December 1984, for a Best Of titled “The Very Beast Of Spitting Image”.3 Series 2 proper then arrived in January 1985. And the team had a dilemma. As Tooth and Claw describes:

“When the second series got underway, the problem, from Spitting Image’s point of view, was how to keep stirring without actually landing in the soup.”

In other words: how can Spitting Image keep prodding Norris and the IBA about flash frames, without actually having lawyers swooping in from overhead?

The answer resulted in some of my favourite material Spitting Image ever broadcast. Episode 2.4 on the 27th January 1985 starts off with the following message:

Later in the episode, we get a genuine flash frame as part of a brilliant sketch, which Tooth and Claw confirms was specifically cleared by the IBA before transmission. Hence it survives on the DVD release of the second series intact:

Having a real flash frame and then acknowledging it, rewinding it, and repeating it so nobody could accuse the programme of surreptitious messaging is really a bloody clever idea.4

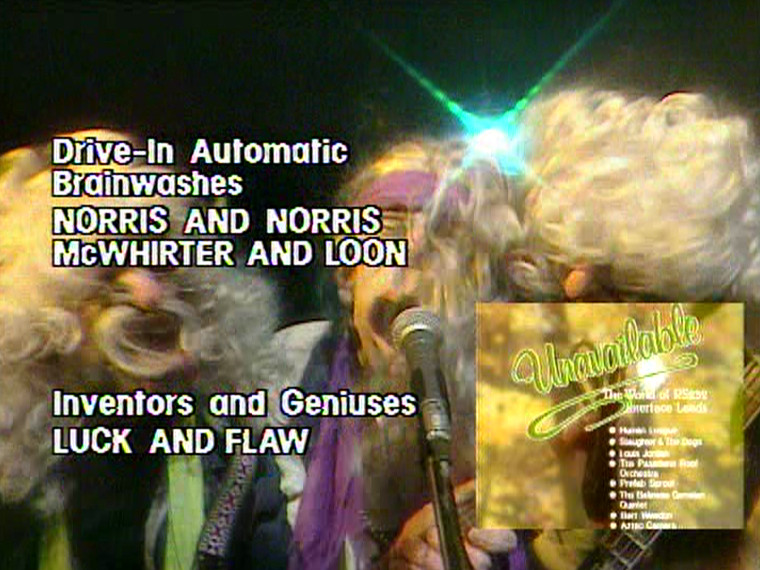

As for Norris McWhirter himself, the show wasn’t going to leave him alone either. As Tooth and Claw says:

“McWhirter himself posed more of a problem. They had toyed with the idea of making a puppet of him but he did not seem quite important enough. The fall-back option that was adopted was to spray the programme with his Christian name – ‘You’re just a silly old Norris’ sort of stuff.”

“Spray” might be a slight over-exaggeration, but the show does indeed do a little of this. Episode 2.6 on the 10th February opens with Margaret Thatcher saying “We’ve got to get rid of Clark. He’s a complete Norris.” Then, at the end of the show, we get this in the closing credits:

It seems somehow inevitable in this febrile environment that Spitting Image would land itself in genuine trouble again. Episode 2.7, on the 24th February5, turned out to be the boiling point.

Things start normally enough, with a quiz show parody using the catchphrase “Up your Norris Horace”. But it was an item in the second half of the show which really caused the mess. Tooth and Claw:

“It was part of this silly but pleasurable tradition that the director John Stroud came to Lloyd with a suggestion. They had a quickfire musical item going down called the ‘Big Busters’, based on the idea that mammaries will sell everything, and they could just drop Norris, with boobs, into that. It would not be a flash-frame, but something very short. Lloyd thought the idea less than outstanding, but why not?”

This sketch is present on the Series 2 DVD, but not in its original transmitted version. For your delectation and delight, however, I’ve managed to source another off-air. Here’s the sketch that landed Spitting Image in court.

Norris is at 26 seconds in, for six frames. And here’s a comparison of the offending shot in the original broadcast version, and the edit released on DVD:

Original broadcast

DVD

CHOOSE YOUR FIGHTER.

Much like the 1984 “good in bed” flash frame, this change almost certainly wasn’t made for the DVD release itself. Instead, it was probably done back in 1985 to the original master tape, to avoid any chance of compounding the legal problems with an accidental repeat. As with that first errant flash frame, there’s no evidence that any of the Granada Plus showings included it.

Tooth and Claw:

“Now it was McWhirter’s turn. Having timed his androgynous moment at .24 of a second he was satisfied this fell within the scope of the Broadcasting Act. His next move was to take out a summons against John Whitney, the IBA chief, for allegedly being in breach of his statutory duty to stop subliminal messages.”

It is worth pointing out that McWhirter got his calculations absolutely correct here. His visage was seen for six frames; 6 divided by 25 is indeed .24 of a second.6

Sadly, this is pretty much all we get with this story from Tooth and Claw, which so far has been our bible as to exactly what happened with the flash frames nonsense. Instead, the topic is quickly wrapped up with the following:

“John Lloyd’s sky was soon dark with angry memos from Birmingham executives feeling he’d dropped them in it again. Ultimately, in 1986, McWhirter’s summons was quashed by the courts, but it had been a worrying time for all concerned.”

Which is slightly strange. Sure, Tooth and Claw was published in 1986, the same year McWhirter failed in his proceedings against the IBA. But if there was time to tell us what the end game was, however briefly, surely it could have provided a little more detail? It’s an odd little wrinkle, especially as the book itself calls the topic the show’s “longest running legal saga”, and so explicitly acknowledges its importance.

It’s all very well telling us McWhirter’s summons was “quashed by the courts”; it doesn’t actually say why.

Let’s find out.

* * *

One interesting thing immediately presents itself. With the 1984 Spitting Image flash frame, the topic found its way into the newspapers virtually immediately. With this one, there was a delay of a fair few months. The flash frame was broadcast on the 24th February 1985; the first report I can find is from the Evening Standard on the 2nd July, over four months later.

Under the headline “Forbidden Images caught in slow-motion”, it gives a brief precis of the 1984 flash frame7, and then continues:

“Three weeks ago McWhirter was shown another videotape of a more recent Image programme in which his own features were superimposed on a naked woman’s body, presumably the lads’ idea of settling the score. At normal speed the flash lasts just 0.24 of a second.

This morning McWhirter applied at Horseferry Road magistrate’s court for another summons which was granted – Round Two. We now proceed to the next courtroom where the case will be prosecuted against Whitney.

Spitting Image producer John Lloyd admits that a flash frame, as he calls it, was used as a joke in the programme’s first series “basically saying hello and making a few jokes about comedy writers. We were rapped over the knuckles but the lawyers said it wasn’t breaking the Act because it wasn’t done with intent to influence viewers.” Despite McWhirter’s claim, he denies that subliminal message [sic] have been used since.

Tediously detailed examination of all the programmes will show whether and how many images have been flashed by the Image-makers, but in any case the first prosecution of an IBA chief deserves its place in the Guinness Book of Records.”

I would suggest that the term “naked woman” rather oversells what happened here; “topless woman” would be more accurate.8 It’s also worth reiterating that regardless of what conversations John Lloyd was having with lawyers, intent never become a useful legal question in any actual proceedings. It’s also worth noting that the first flash frames incident never even got to court.

The following day, The Daily Telegraph reported more on the case, under the headline “IBA faces legal tangle over quick flashes”:

“The Independent Broadcasting Authority, guardians of the ITV network, found themselves in a legal tangle over a series of quick flashes yesterday.

Mr John Whitney, its director-general, was named on a summons taken out at Horseferry Road court by Mr Norris McWhirter, the legal campaigner, alleging that the authority had permitted the transmission of “subliminal” messages.

He claimed two such transmissions had been included within a year in ITV’s satirical puppet series, “Spitting Image”.

The most recent one showed his features superimposed on the body of a naked, busty female. Lasting fractionally under a quarter of a second it was invisible to the normal viewing eye.

Mr McWhirter, 59, explained: “I would have known nothing about this but for my 14-year-old nephew, who had taped the programme and was playing it back using the ‘freeze-frame’ device.

“Suddenly, he said “look, it’s Uncle Norris,” and there was a picture of my face cut off at the neck and beneath it the torso of a naked, big-busted woman.9

“We timed the sequence at 0.24 seconds, which definitely brings it within the scope of the Television Act.”

This report, of McWhirter’s nephew reporting the image to him, is also mentioned in Tooth and Claw. Other people have discussed this elsewhere10, but it is of course extremely funny to imagine Norris’ nephew carefully studying Big Busters on freeze-frame. Well done embarrassing the poor kid in the papers though, Norris!

John Whitney, for his part, was keen for this not to come to court. On the 9th August, the Daily Post reported:

“The IBA yesterday asked TV personality Norris McWhirter to drop his legal action over a split-second appearance in the Spitting Image satire show.

Director General John Whitney said guidance was being issued to all ITV companies and Channel 4 reaffirming legal restrictions on using “subliminal” images. […]

Yesterday Mr Whitney urged him in a letter to scrap his legal battle in the light of the IBA’s guidance.

“I hope you will now feel the guidance we have issued meets the substance of your objections.”

And McWhirter’s response?

“But Mr McWhirter said in a statement he was “not readily persuaded that mere notes of guidance” were sufficient.

He said: “A prosecution might end up being helpful to the IBA in their statutory duty to preserve the rule of law.”

Whatever my opinions of McWhirter, I find that last statement on a par with John Lloyd’s statement on the first flash frame that “Nobody knew it was illegal as such”. Yes, how helpful of Norris to take the IBA to court. He was only doing it out of the goodness of his heart.

At this point, the legal process begins for real, and for the rest of 1985 the case trundled through the various court processes. I’m going to skip most of this toing and froing, which might be fun if we were doing a legal soap opera on the case, but risks obscuring our main point. Instead, let’s get to the actual ruling, on the 30th January 1986.

Of course, Tooth and Claw blew our load early, and the outcome is not a surprise. The Telegraph reported the next day, under “McWhirter Loses TV Nude Case”:

“The screening of a nude “subliminal” image on the satirical “Spitting Images” [sic] TV programme was not a criminal offence under the 1981 Broadcasting Act, two judges ruled in the High Court, London, yesterday.

The judges stopped the legal campaigner, Mr Norris McWhirter, 60, from prosecuting the Independent Broadcasting Authority over the image which he had alleged showed “a grotesque and ridiculing image” of his face superimposed on the top of a naked woman’s body.

Lord Justice Lloyd and Mr Justice Skinner sitting in the Queen’s Bench Divisional Court, granted the IBA orders quashing Mr McWhirter’s private summons issued by Horseferry Road magistrates, London, last July and banning all further proceedings.

Mr McWhirter, co-founder of the Guinness Book of Records, had claimed the image – broadcast between January and March last year11 – exploited the possibility of conveying a message to influence the minds of members of the public without their being aware of what had been done – in breach of the Broadcasting Act.

Lord Justice Lloyd said the act imposed only a mandatory duty on the IBA to satisfy themselves that programmes did not include subliminal images.

“It does not create a criminal offence,” he said. To decide otherwise would be “to fly in the face of common sense”.

Mr McWhirter was refused leave to appeal to the House of Lords. He said afterwards he intended to apply directly to the Lords for leave. […]

His counsel, Mr Francis Bennion told the court McWhirter had started proceedings “out of a sense of public duty and not out of a sense of personal complaint about what was done to him.”

Handing out photographs of the offending frame after losing his case, Mr McWhirter said “The reason I took criminal rather than civil proceedings [was] because transmission of subliminal images, which is essentially deceitful, has been repeated.”

Mr McWhirter has to pay the legal costs of yesterday’s High Court hearing.”

The image of Norris McWhirter personally handing out pictures of a topless woman with his head pasted on is quite possibly the funniest thing to come out of this entire affair.

Still, there remains something rather puzzling about all this. In the reporting of the case in the papers at the time, we are told that the reason the hearing came down in favour of the IBA was because no criminal offence had taken place. But at first glance, this seems hard to understand. After all, it was an IBA man, Stephen Murphy, who first called up John Lloyd the previous year and said “My dear boy, you’ve broken the law.” The wording of the Broadcasting Act seems clear enough. To a layperson like myself, and presumably to most of you lot, it all seems very odd. Why had no criminal offence actually taken place?

For years, I assumed that this was a simple matter of duration: that six frames simply could not be considered a subliminal image, unlike the single flash from 1984. It’s certainly the hint Tooth and Claw gives: “It would not be a flash-frame, but something very short.” But it turns out it’s nothing to do with that whatsoever.

To get the true answer, we have to turn to the case report: “Regina v. Horseferry Road Justices, Ex parte Independent Broadcasting Authority” (1987)12. This explains, in surprisingly straightforward terms, exactly why the 1985 flash was not judged to be a criminal offence:

“There are many statutes which impose duties and prohibitions upon statutory bodies. Clearly many such provisions do not create criminal offences if they are contravened. The modern practice is that when Parliament intends that the contravention of a statute should constitute a criminal offence, it expressly so provides and the mode of trial and maximum penalties are set out.

One illustration will suffice to demonstrate where a statute is silent as to the remedy for breach of the duties contained therein, Parliament cannot have intended that the breach should in every case be punishable on indictment with an unlimited fine: the Civil Aviation Act 1982 imposes on the Civil Aviation Authority duties to perform various functions, yet it has never been suggested, nor could it be suggested, that failure to perform those duties would render the authority liable to criminal sanctions.”

In other words: if the Broadcasting Act 1981 wanted to make a criminal offence of any contravention of section 4(3) regarding subliminal images, they needed to be a damn sight more explicit as to exactly what they expected the courts to do about it. As it stands, the section can be regarded merely as a strong suggestion, with no legal outcome it isn’t followed, at least in terms of criminal law.

Which means that the question as to whether six frames counts as a subliminal image or not turns out to be entirely irrelevant – the duration of the image doesn’t enter into the above ruling at all. In fact, it retrospectively means that Spitting Image‘s single-frame flash in June 1984 wasn’t a criminal offence either!

There is something extremely amusing about McWhirter endlessly claiming his crusades were simply about the rule of law, being being undone by, erm, the rule of law. Although I think we’ve now had enough fun at McWhirter’s expense. It certainly wouldn’t be even more amusing if strict adherence to the law gave him one final kicking.

The Scotsman, 11th July, “McWhirter time-barred”:

“Mr Norris McWhirter yesterday undertook to continue his battle against the transmission of subliminal images on television, after his attempt to bring a private prosecution against the Independent Broadcasting Authority failed in the House of Lords.

A committee of three Law Lords refused to allow Mr McWhirter to argue his case because his petition for leave to appeal was one day late.”

No, that isn’t funny in the slightest.

* * *

And that pretty much wraps up all the fun with Spitting Image. Next time, we return to The Young Ones. But surely the trouble for Jackson and company was over, after all their flash frames nonsense in 1984?

Not quite. Is it normal for a comedy show to be slagged off in Parliament?

With thanks to Nigel Hill and @inqusitor for the original Spitting Image broadcasts, Ernest Malley for legal research, and Paul Hayes, Tanya Jones, Darrell Maclaine, Mike Scott and John Williams for editorial advice.

All of this was due to the launch of Independent Local Radio in 1973, which broadened the scope of the old ITA. ↩

It didn’t stop the Cambridge Evening News warning its readers to “Beware of Flash-Frames” in their listings. ↩

This, and all subsequent Spitting Image specials, never made it onto the DVD releases, meaning that they’ve been all but erased from history. ↩

Though for my money, the squealing of the IBA voice at the end of the sketch is what makes it. “Will someone arrest me for recording the programme? It’s totally illegal!” ↩

IMDB gives the date as the 17th February, but the DVD release states it was the 24th. On the 17th, ITV were showing an extended South Bank Show on David Lean. ↩

Here’s something which always ticks away at the back of my mind with the McWhirters, but it’s a little pop psychology, so I’m going to hide it away in this footnote. We can debate for hours how much their campaign against subliminal images was in good faith, and how much was just political manoeuvring. But with their genuine interest in the smallest and largest of something – hence The Guinness Book of Records – is it not possible that it’s also a symptom of being fascinated by the smallest possible length of something?

That, of course, doesn’t explain their courtroom antics. But it is perhaps one reason why the topic grabbed hold of their brains, and refused to let go. ↩

But not, frankly, a very accurate one. “Last year McWhirter discovered that one Spitting Image programme had flashed (mot juste, almost) a message about the sexual prowess of Roger Law and Peter Fluck, makers of the programme.” The flash did no such thing, of course; it simply mentioned “script writers”, and Fluck and Law had no say in the programme’s scripts.

One huge problem with this whole topic is that even at the time, the papers simply did not report on the case very accurately. Partly because subliminal messages are a topic which is inherently difficult to report on, but partly because so many journalists who write about television simply don’t understand TV production. ↩

So much of the reporting of this case is faintly hysterical when compared to what was actually broadcast. ↩

Is it only me who doesn’t think the model has particularly large breasts? Maybe I’ve just been spoilt. ↩

For instance, in Law’s Strangest Cases by Peter Seddon. Not that the book gets a lot else correct about this case, but I’ll leave that for now, or you’ll end up with a 1,000 word footnote. ↩

This is a peculiar point, incidentally. The official court documents suggest the image was broadcast “on a date unknown between 23 January and 24 March 1985”. The actual date of the image was broadcast on the 24th February. So it’s technically accurate, but ludicrously fuzzy. Could Norris and his legal team really not figure out when the episode was actually broadcast? ↩

The 1987 date refers to when the case report was published; the final hearings were in January 1986. ↩

4 comments

James on 29 October 2023 @ 4pm

Thank you, Norris’ nephew. And thanks to his parents, for purchasing a high quality VHS machine. I can imagine how much fun school was the next day.

Gareth Randall on 30 October 2023 @ 3pm

This has reminded me that I was unwittingly involved in a complaint to Ofcom about subliminal advertising in 2002. I’d produced the launch campaign for the first series of I’m A Celebrity (a show for which ITV had no great hopes, believe it or not, and hence wasn’t willing to spend much on launching) and among the list of items I was required to produce was a 12-frame break optical.

I decided to go with still images of the celebs pulling a “scared” face while holding a card on which we could later add things like “Help!”

and “Get me out of here!”. Some celebs turned out to be better at pulling a “scared” face than others, but that’s another story.

The final opticals were just those stills with an accompanying “zap” sound effect. They weren’t used in all ITV regions because some of them had ageing playout systems that couldn’t cope with events as short as 12 frames.

Some weeks later we discovered that at least one complaint had been made to Ofcom about the opticals being subliminal advertising. Ofcom’s investigation dismissed it on the grounds (IIRC) that the sound effect helped actively draw viewers’ attention to the opticals and therefore they couldn’t be considered an attempt to influence viewers without them being aware.

John J. Hoare on 30 October 2023 @ 4pm

In BBC playout now, the shortest thing we play routinely is 3″ blips. I’m trying to remember if we used to do 2″ ones. I can check when I’m back in work, the old ones are hanging around on the system somewhere.

I think TV has generally moved away from material that short. When I used to work on Channel 5 we had breakflashes between each ad (12 frames?), but they’re long gone. That caused weirdness when different numbers of ads ran in different regions (30″/30″ v. 20″/20″/20″, for instance) , as the timings wouldn’t match up because of the different number of breakflashes. Meaning the region with the least number of commercials would have to hang on the final frame at the end of the break until everything caught up.

Of course, ad regions on Channel 5 are long gone too…

Martin Fenton on 11 November 2023 @ 2pm

My father was absolutely horrified to discover that they were still giving Norris McWhirter airtime on Children’s BBC in the 1980s.