The origins of Red Dwarf are oft-told. Radio 4 sketch show, Son of Cliché, Dave Hollins, job done, right?

And true, one of the first sparks of life of something which turned into Red Dwarf appeared on Radio 4 on the 30th August 1983, with the very first sketch of Dave Hollins: Space Cadet.1

Download “Dave Hollins: Space Cadet – The Strange Planet You Shouldn’t Really Land On” (MP3, 3:41)

Nick Maloney’s corpsing at the end of that sketch is brilliant.

Still, Dave Hollins wasn’t a running sketch in that first series of Son of Cliché. We’d have to wait until the following year for that privilege. And when it did come back, on the 10th November 1984, I would argue that it was as something far more recognisable as Red Dwarf.

Download “Dave Hollins: Space Cadet – Norweb” (MP3, 3:35)

“Jan Vogels” in the first sketch did nearly made it into Red Dwarf – most notably, a far shorter version is present in the US pilot (“You know a guy called Harry Johnson?”).2 But that second Dave Hollins sketch is stuffed with ideas which later found a home in actual, broadcast Dwarf.

For instance, compare the opening Hollins joke to a Holly gag in “Queeg”, 4th October 1988:

DAVE HOLLINS: My biggest problem is going space-crazy through loneliness. The only thing that keeps me sane is my collection of onions.

HOLLY: Our biggest enemy is going space crazy through loneliness. The only thing that helps me maintain my slender grip on reality is the friendship I share with my collection of singing potatoes.

Or how about this in “Confidence & Paranoia”, 14th March 1988:

DAVE HOLLINS: I have decided to build an android in the image of a woman. A perfectly functioning robot, capable of abstract thought and independent decision making. But I don’t know how. Jesus, I don’t even know what to make the nose out of.

HOLLY: I was thinking it might help pass the time if I created a perfectly functioning replica of a woman, capable of independent decision-making and abstract thought, and absolutely undetectable from the real thing.

LISTER: (eagerly) Why don’t ya?

HOLLY: I don’t know how. I wouldn’t even know how to make the nose.

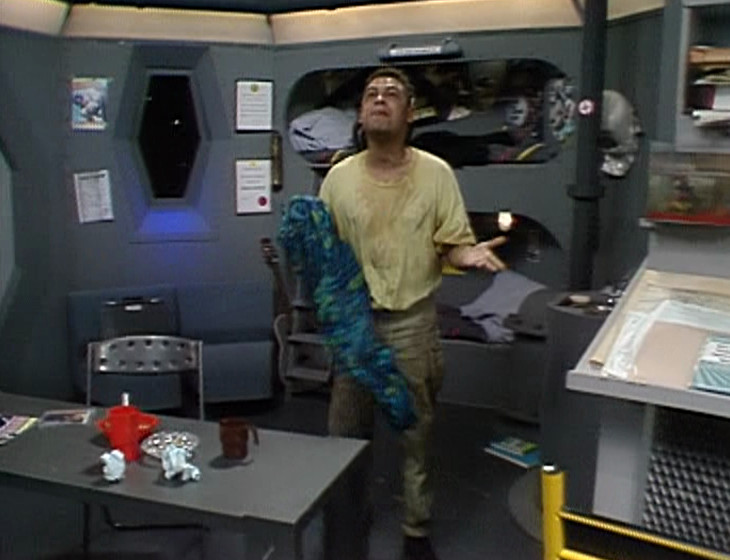

Most obviously, the whole Norweb Federation section is reused in this scene from “Me²”, 21st March 1988:

The fact that it had to be turned from a “real” idea in Son of Cliché, to an April Fool joke in Red Dwarf, is a lovely piece of writing that ensures Grant Naylor could reuse a bit of their old sketch material, but not at the expense of Red Dwarf‘s more believable universe.

But perhaps the most important thing they took from that second Dave Hollins sketch is HAB himself. The fundamental problem with creating Red Dwarf was how to write a sitcom about the last human being alive, while still having, y’know, those pesky characters that people seem to think are so important. Grant Naylor answered the problem with a life form who evolved from his cat, a hologram simulation of one of the dead crew, and later, a service mechanoid rescued from the crashed vessel the Nova 5.

But a key part character from the very beginning was the ship’s computer: renamed from HAB to Holly.

* * *

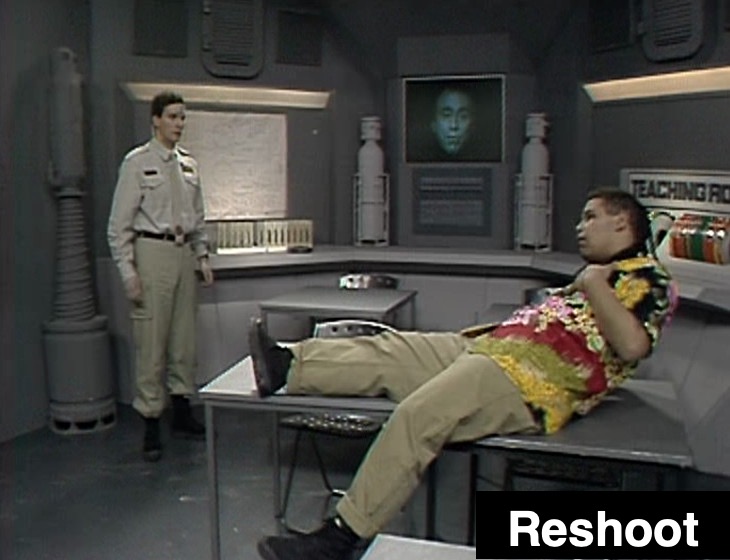

In the beginning, the radio origins of Holly were all too apparent. While Dave Hollins gained a body and face when he changed into Dave Lister, Holly was supposed to remain just a voice.

Unfortunately, they had reckoned without Norman Lovett’s whinging. Director Ed Bye takes up the story:

ED BYE: Rob and Doug and I made the decision that it’d be better to see Norman rather than just hear him, because he’s got a great lugubrious face.

NORMAN LOVETT: Initially the money was low because it was a voiceover, so they can get away with paying you peanuts for that.

ROB GRANT: Norman had been banging on from the start saying “Get my face on-screen, that’s the money…”

NORMAN LOVETT: So I kept moaning and whinging about this. I said “Why have I got to do a voiceover in a TV show? Why can’t you see this face, and why can’t this computer called Holly look like this bloke here?” By the time we’d recorded the third episode of the first series, it had been agreed that we would see Holly, and we’d go and reshoot some of the bits for the first and second and third episodes…“The Beginning”, Series 1 documentary, The Bodysnatcher Collection (2007)

The above story – in various slight variations – has gone down in Red Dwarf lore. Norm endlessly complained that Holly should be in-vision, the powers that be eventually agreed, and they went back and did some reshoots to add his face to the early episodes. The real horror arises when you consider that due to the electricians’ strike, where Series 1 was nearly entirely rehearsed but never actually recorded, Norm might well have been on his ninth week of moaning about this, rather than the third. Try not to let that shrivel your soul too much.)

However, what hasn’t been done is going back to examine those early episodes in detail, to see exactly how those reshoots worked. And when you do, you spot a few interesting details which haven’t been widely talked about.

Let’s take a look. Doing this takes a certain amount of extrapolation; without access to the proper production paperwork, we have to do a bit of stretching and join some dots along the way. But I think the below makes sense. Obviously, to get any kind of idea of how this was done, we have to take the episodes in production order rather than broadcast order.

The End (Original Shoot)

RX: 26th/27th September 1987 • TX: 15th February 1988

As detailed in past articles, much of the first episode of Red Dwarf was shot twice: once at the beginning of production, and then again at the very end, in order to improve what was seen as a slightly dodgy start to the series. Luckily, the aforementioned Bodysnatcher DVD release contains a wonderful extra called “The Original Assembly”, which consists of a version of “The End” using only footage from its very first recording session.

Which makes articles like this possible. And surprise! The very first attempt at “The End” contains no visuals of Holly at all. Of course.

It’s instructive, however, to look at how the crew talk to Holly in the episode. Both at McIntyre’s funeral, and when Lister and Rimmer receive the message for the ‘Welcome Back George McIntyre Reception’, they gaze upwards, listening to Holly’s disembodied voice.

In fact, it’s easy to imagine Red Dwarf treating Holly exactly like this. Sure, we’d lose some great stuff, but with Rob and Doug’s background in radio, they could happily have written funny stuff for just a voice.

But things wouldn’t stay like that for long. Onto the second episode recorded.

Balance of Power

RX: 3rd/4th October 1987 • TX: 29th February 1988

Ah-ha. The reshoots start in earnest.

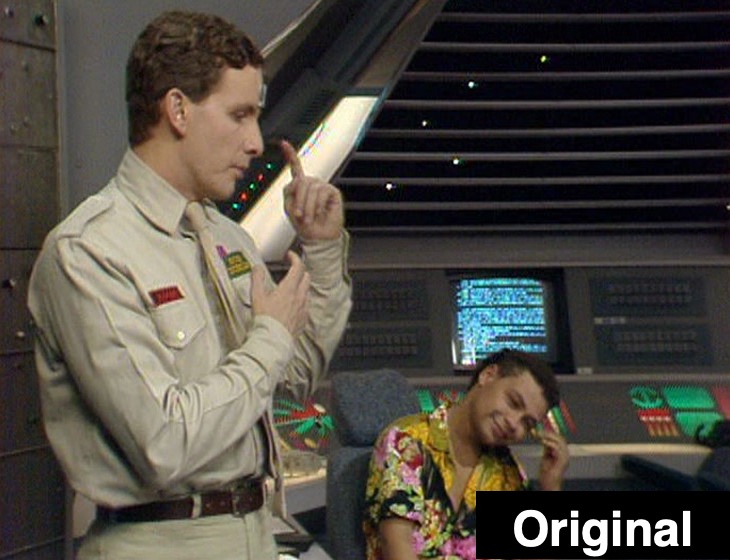

Firstly, we have the first bunkroom scene between Lister and Holly. As in the original version of “The End”, Lister spends the scene talking to a disembodied voice and looking upwards; there’s no sign of Holly on the monitor.

But what’s this? There’s a couple of shots of Holly in-vision!

Presumably this scene was originally shot with Holly as just a voice, and then they went back later and did a couple of cutaways of Norman to stick in there. Which, it has to be said, works very well: the cutaways could have felt awkward, but the scene feels perfectly natural. It’s certainly not obvious that they are cutaways shot after-the-fact.

Meanwhile, the bunkroom scene between Rimmer and Holly is similar, with Rimmer talking to a disembodied voice. Unlike the first scene, however, there is no attempt to disguise this with cutaways shot later:

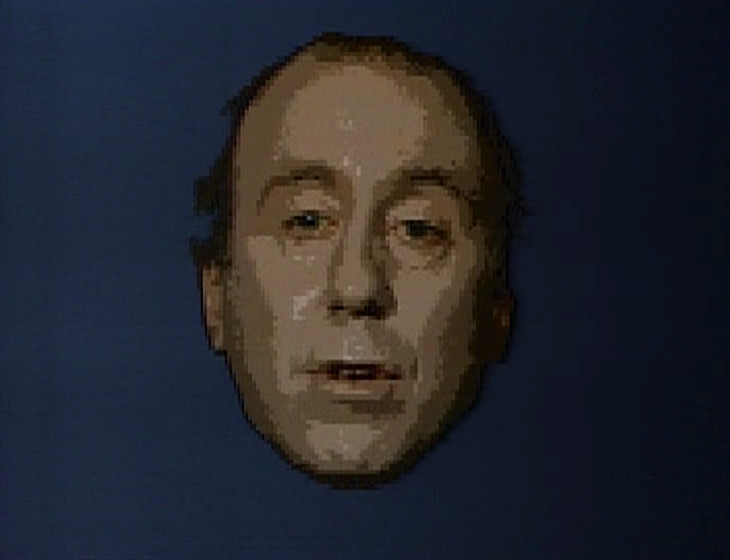

However, straight afterwards, we cut to Cat in the Drive Room. And whoa ho ho, what’s all this? Holly on the monitors? This hasn’t happened before now!

Indeed, this scene is key to establishing Holly as a visual character. This is disguised somewhat by reshoots and the jumbling of the episode order. But in many ways, here is where Holly is born. Just take a look at the scene again, with this in mind – for the first time, the dialogue specifically references how Holly looks:

RIMMER: Holly, as senior rank aboard this ship, I order you to tell me where he is.

HOLLY: I’ve told you, I can’t.

RIMMER: Holly, that’s an order! You stupid ugly goit.

HOLLY: Ugly? I’ll have you know I chose this face out of the billions available cos it happened to be the face of the greatest and most prolific lover who ever lived. [Holly sticks his tongue out]

RIMMER: Really? Well, he must have operated in the dark a lot.

HOLLY: You what?

There is something delicious about Rob and Doug responding to Norm moaning that he should be in-vision by writing dialogue where Rimmer outright calls him ugly.

This won’t have been shot during the original “Balance of Power” recording sessions. If it had been, then Holly would surely be in-vision properly elsewhere in the episode. Besides, most accounts of these shenanigans state that at least the first two episodes were recorded with Holly as just a voice. Which leaves us with an interesting question: surely there was an original version of this scene recorded, with Holly out of vision?

Sadly, it didn’t show up on the Series 1 deleted scenes on the DVD releases. Bugger.

Waiting for God

RX: 10th/11th October 1987 • TX: 7th March 1988

Third recording session of the series, and things have settled down somewhat. We have Holly present and correct visually in the Drive Room:

In the Observation Room:

And we even have our very first example of a DVE being used to place Holly into a set without a monitor:

Bit-by-bit, the production is figuring out how to make Holly work as a visual character.

There is one aspect, however, where the show hasn’t quite figured things out: the bunkroom. The show is still alarmingly inconsistent when it comes to visualising Holly in the key set of the show. We do get the following when Lister walks back into the bunkroom, as Holly is explaining the fate of the Cat people:

But this is the only shot of Holly on the monitor in the bunkroom in the whole show; we never get to see him in a wide. It’s a very half-hearted stab at establishing Holly’s presence in the set. The show is nearly there… but not quite.

One further thing: in a quote earlier in this article, Norman indicates that the decision to add him visually to the show happened after the third episode recorded. I don’t think this is true: there is simply too much Holly material in “Waiting for God” for that to be credible, especially considering the reshoots they would also have to do for “The End”.

Rob Grant gives a more plausible timeframe in this interview:

“Well, for some odd reason, the BBC had paid for seven shows, but only wanted six, so we had a spare week at the end of the run to touch up any bits we didn’t like. That included putting Holly in shot on screens on the first couple of shows, because we’d only introduced him after the first few shows.”

I trust Rob Grant more than I do Norman Lovett. So the decision to put Holly in-vision was almost certainly taken between the recording of “Balance of Power” and “Waiting for God”.

Future Echoes

RX: 17th/18th October 1987 • TX: 22nd February 1988

And the oddities continue into “Future Echoes”.

Firstly we have, yet again, a single attempt at integrating Holly’s visage into the bunkroom set, with the answerphone message he leaves for Rimmer:

It has always bloody annoyed me that the still of Holly is different in the wide shot and the close-up, and this article is finally the ideal vehicle to express my annoyance. I AM ANNOYED.

We also get something brand new: when Holly is trying to navigate the ship at light speed, we get the show messing around with the pixellation to indicate his frazzled brain. This is followed shortly afterwards by the first time Norman does anything other than stare straight ahead at the camera. “Gordon Bennett, that was a close one…”

In other words: this is the very first time the show experiments with any kind of additional effect on Holly’s visuals in order to help tell the story, or make a joke.

Still, aside from the answerphone message gag above, the bunkroom scenes in this episode have the crew talking, and then we cut to a close-up of Holly. We never actually see him on the monitor in the bunkroom itself.

Which is odd, because when Rimmer calls Holly a goit, he directly points his finger at the monitor in the bunkroom. So although we don’t see him on there in the wide shots in this episode, he’s clearly implied to be present on that monitor by this point during conversations!

Which is at best peculiar, and is totally different to the way the crew have talked “upwards” to Holly in previous episodes. Again, we’re really in a transitional state here.

Mind you, transitional state or not, it’s very interesting that “Future Echoes” was bumped up from fourth to second episode in the run. Of course it’s a great episode; one of the strongest of the first series. But the shifting of this episode also has another effect: it establishes Holly as a more successful and ever-present visual entity earlier on in the series than would otherwise be the case.

It certainly helps disguise some of the fudging that affects “Balance of Power”.

Confidence & Paranoia

RX: 24th/25th October 1987 • TX: 14th March 1988

There are very few developments regarding Holly in “Confidence & Paranoia”. So instead, here’s something from its opening scene which I would like to ponder. You remember the one. The one where Holly keeps interrupting Lister as he’s trying to watch the film.

The question: how would this have played out as originally scripted, with Holly out of vision? Would the video have just kept dipping to black as Holly spoke as a disembodied voice? Or, perhaps more likely, would the film have continued, and Holly just spoke over the top of it? Or is it possible that this scene wasn’t in the original script at all, and was added when the decision was made to put Norm in-vision?

It’s at this point that I’d love to see copies of the scripts brought into Red Dwarf‘s first set of rehearsals. There would surely be all kinds of revelations about this stuff.

Me²

RX: 1st November 1987 • TX: 21st March 1988

“Me²” signifies a great step forward for Red Dwarf. Nah, I’m not talking about character development for Rimmer. Fuck that needy gobshite.

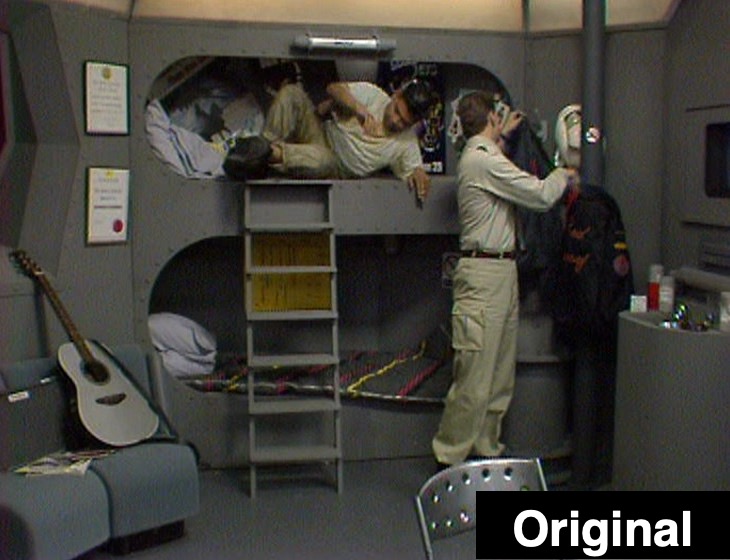

No, I’m talking about the following bunkroom scene between Lister and Holly, about the Norweb Federation. The one we saw at the beginning of this article.

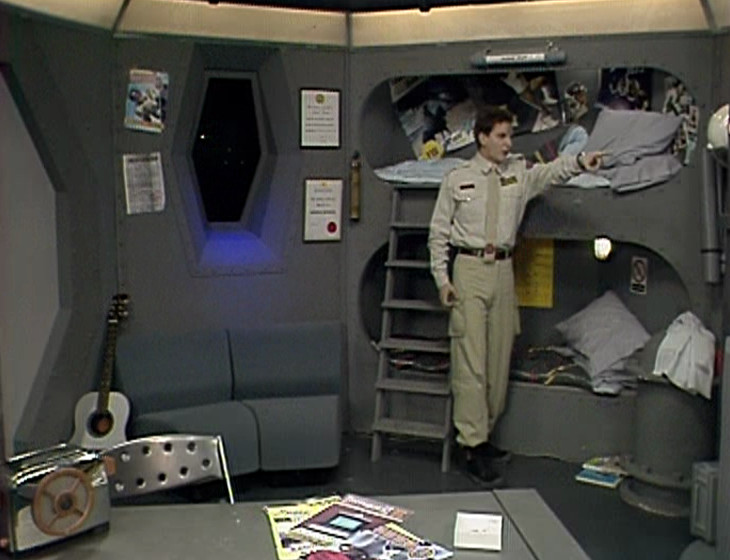

This is the first, honest-to-goodness scene where we actually see Holly properly on the bunkroom set monitor, and Lister has a proper conversation with the screen. Sure, there are hints of it in the past – Rimmer’s answerphone message in “Future Echoes”, and the brief close-up in “Waiting for God” – but here is where it all clicks together. In the penultimate recording session for Series 1. Awfully late, really.

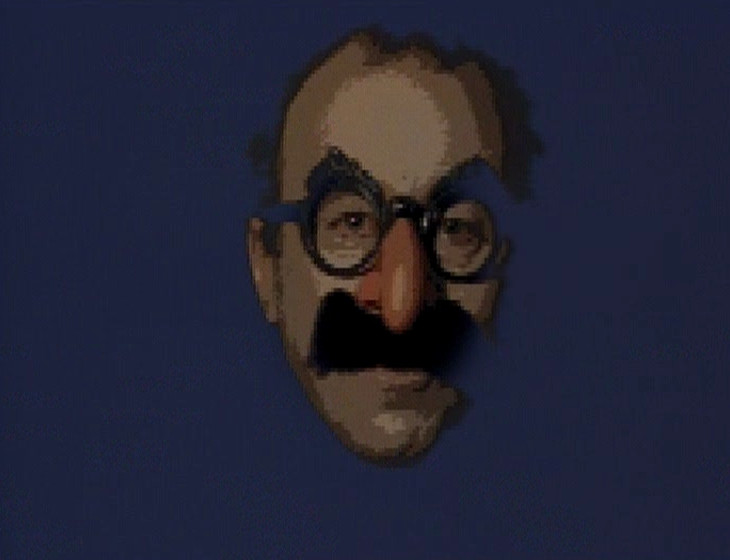

And when Holly appears with those glasses, and says the immortal words “April Fool”…

…I mean, it’s not like you couldn’t do that joke with Holly as a mere voice. But surely the moment wouldn’t be remotely as satisfying.

The End (Reshoot)

RX: 7th/8th November 1987 • TX: 15th February 1988

We now reach the really interesting bit. As mentioned earlier in this article, the seventh week of production wasn’t used for shooting another episode; it was used for doing pick-ups for previous weeks. Including reshooting at least half of “The End”.

Which means: plenty of putting Norman Lovett in-vision, where in the original recording he had just been a voice. The following gives an idea of how extensive this is, and this isn’t even every single example I could give.

Of the above I particularly want to single out this shot, from the very first bunkroom scene in “The End” as broadcast:

This shot, I believe, is the one which sells Holly’s position in the bunkroom, on the monitor. And it stays in the mind – perhaps subconsciously – and gets you right through all the transitional weirdness throughout the rest of the series.

It gets you through never seeing Holly on the screen in the second bunkroom scene from “The End”, which was taken from the first recording session. It gets you through Rimmer pointing at the screen in “Future Echoes”, even though we don’t see Holly on it. It gets you through all the inconsistent added cutaways in “Balance of Power”. It takes you right through until you get to Me²… where they start doing things “properly” again.

These reshoots, especially for “The End”, really did help Holly become a proper visual character, from the very first episode. For years, I think I understood that in theory. But above is the proof.

Series 2

RX: May – July 1988 • TX: September/October 1988

So is Holly’s journey complete? Far from it. But he’s sure come a hell of a long way, and going through Series 2 episode-by-episode isn’t necessary. However, it’s worth taking a brief look at how Holly’s on-screen role continued to develop.

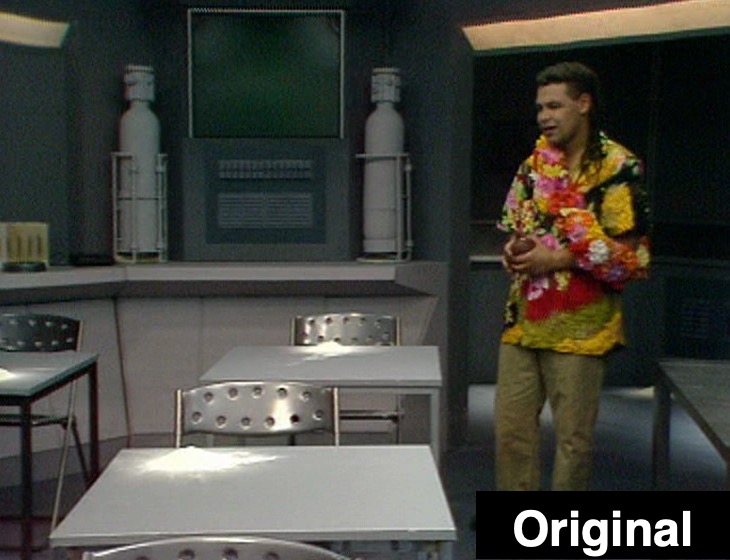

Firstly, “Better Than Life” – and specifically, the first bunkroom scene:

This takes the bunkroom scene between Lister and Holly in Me², and runs with it. Everything suddenly feels natural and right. We’re a long way off from some of the weirdness of Series 1 here.

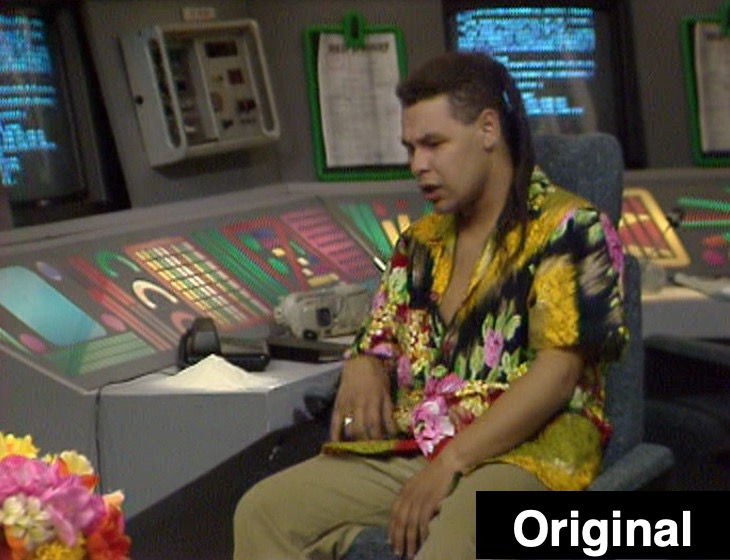

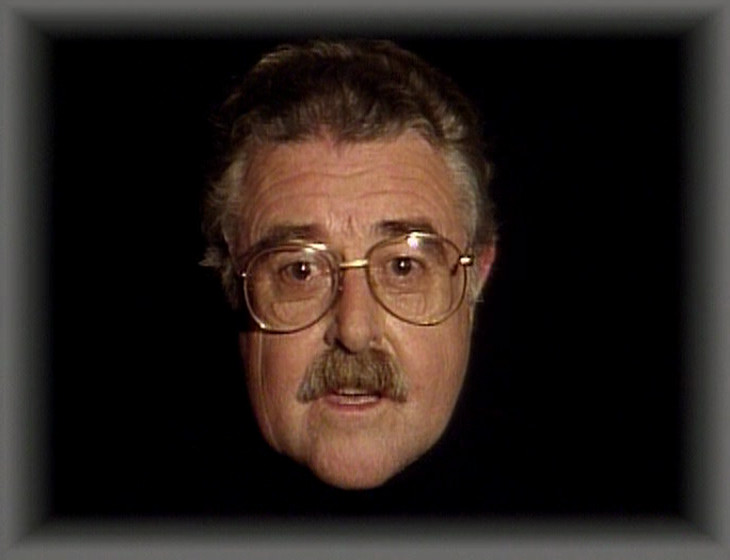

Then there’s the first time we see Gordon, the computer on board the Scott Fitzgerald – and the first time we see another computer in the vein of Holly, an idea which would have lasting repercussions for the series:

“Better Than Life” also shows us the first time Holly becomes portable. (So many new ideas in one episode!)

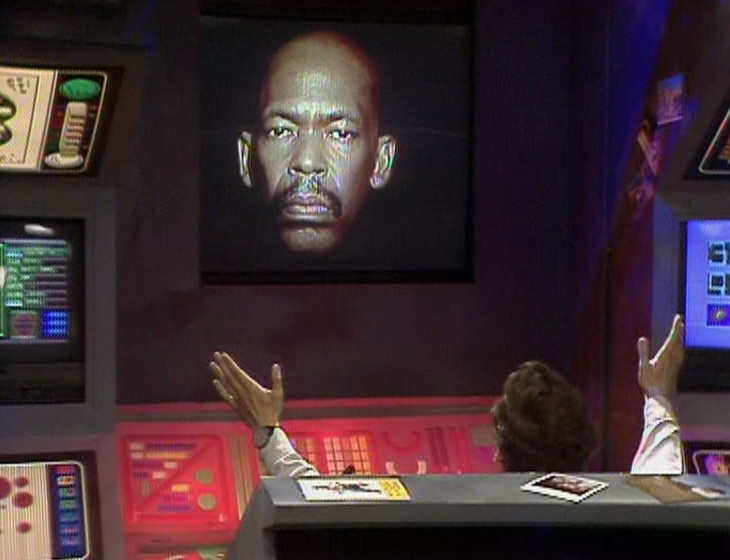

So, bung those last two ideas together – of a different computer like Holly, and Holly becoming portable – and we get a little episode called “Queeg”:

And I just don’t believe “Queeg” is the kind of episode which would ever have been written unless Holly had become a visual character. Two disembodied voices yakking on while Lister looks upset probably wouldn’t have made amazing television. As it is… we got one of the finest half hours of Red Dwarf ever made.

Although we all know the real reason why it was vitally important for Holly to become more than just a voice:

All this careful thought, just to wind up with a wig joke. And isn’t that really the entire spirit of Red Dwarf, encapsulated in one throwaway moment?

Cheers, Norm. For once, your whinging paid off.

A version of this post was first published on Ganymede & Titan in June 2019.

The research for Son of Cliché in this article comes almost entirely from material written in 2003 by Ian Symes, on an early incarnation of Red Dwarf fansite Ganymede & Titan. It’s a measure of how well that research was done that it hasn’t yet been surpassed as reference material for the series. ↩

The 2007 Red Dwarf DVD release The Bodysnatcher Collection also includes a never-shot version of the sketch, recreated using storyboards. ↩