For more on this BBC100 series of posts, read this introduction.

I admit it. When writing about old television, there is often the desire to pick out something obscure nobody has heard of in decades. It’s not an attempt to be clever. (Well, not always, at least.) It’s just that sometimes, you really want to highlight a programme which you feel deserves more attention than it’s been getting lately.

Not today, though. Fawlty Towers, John Cleese and Connie Booth’s masterwork, is as obvious a choice as you can get, if your task is “pick something brilliant that the BBC made in the 1970s”. What is perhaps more surprising is how many lessons the show has for the kind of comedy we could make today. But we’ll get to that in all good time.

The genesis of Fawlty Towers is oft-told, but worth revisiting. Let’s take a short trip back to Torquay, May 1970. The Monty Python team are busy shooting location material for their second series. Unfortunately – or perhaps fortunately for Cleese – they have booked into the Gleneagles hotel, run by a certain Donald Sinclair. He proceeded to be rude to pretty much everybody: insulting Terry Gilliam’s eating habits (“We don’t eat like that in this country!”), staring bemusedly at Michael Palin when being asked for a wake-up call, and most memorably, hiding Eric Idle’s bag behind a wall in case it contained a bomb. “We’ve had a lot of staff problems lately”, stated Sinclair, in an attempted explanation of the latter.

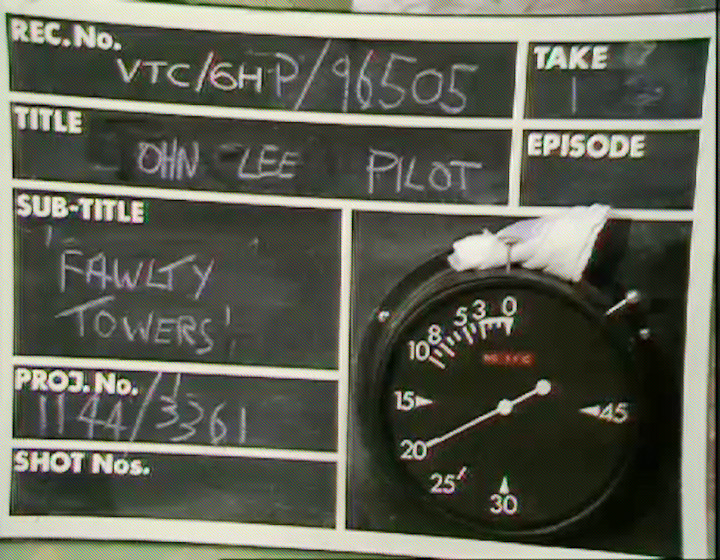

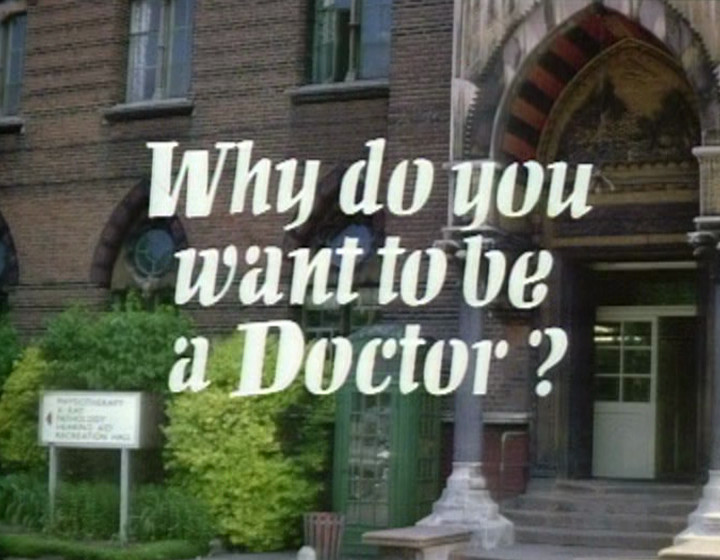

While most of the team moved to a different hotel in the morning, John Cleese stayed… and Connie Booth, his then-wife, joined him a few days later. They sat and watched. And little by little over the years, elements of Sinclair started appearing in John Cleese’s work. In 1971, he wrote an episode of LWT’s Doctor at Large set in a hotel, featuring a proto-Fawlty character called Mr. Clifford. It went down rather well. The character was clearly destined for his own sitcom.

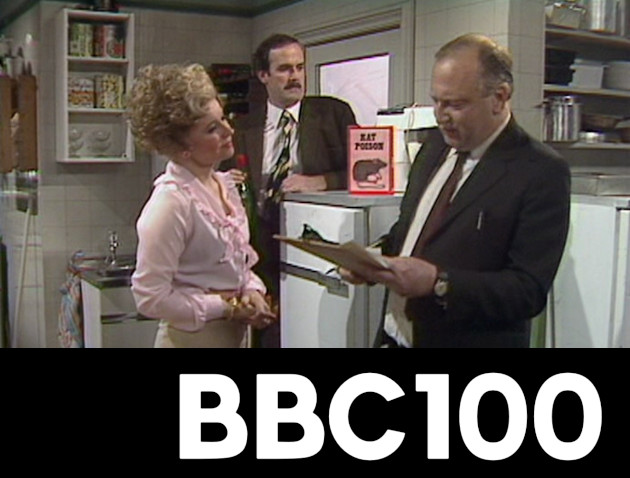

That sitcom was Fawlty Towers. And it’s an incredibly simple series on the face of it, with only four main characters. There’s Basil and Sybil Fawlty, who are uneasily married. There’s Polly the waitress, usually the voice of sanity, and Manuel the waiter, who isn’t. Together they run a hotel, or in Basil’s case, use running a hotel as an excuse to bully the guests. That, in a nutshell, is it.

And yet it isn’t. Fawlty Towers is many things. It’s an exquisitely-written farce. (The camera scripts were twice the size of a typical BBC sitcom of the time.) It’s a character study, particularly of Basil. But it’s also a sitcom where the “sit” is actually important, rather than just a place to put your characters. This is one thing which isn’t appreciated enough: the show is partly a satire of the service industry, where (as Cleese is fond of saying in interviews) hotels are often run for the convenience of the staff instead of the guests. It’s not a topic which sounds immediately entertaining at first glance, but that’s the joy of comedy: it makes the driest of subjects fun. This point was not lost on Cleese, who three years earlier had set up Video Arts, a company which used comedians to make training materials based on that exact principle. Fawlty Towers can genuinely be viewed as a 12-part hotel management training course, if you desire.

Then there’s the true heart of the show: Basil Fawlty, a desperately appalling man. Stuck between strata of the class system, looking down at the “riff-raff”, and desperately fawning upwards at lords or doctors, we laugh at him because most terrible things that happen to him are his own fault. Basil’s problem isn’t just that he is ludicrously uncomfortable in his own skin; it’s that he inflicts the results of that uncomfortableness on everybody else. If he got on with running a hotel instead of sitting in judgement over everybody who walked through the door, his life would be rather more satisfying. But his neuroses are his – and everybody else’s – downfall.

As was standard for sitcoms at the time, Fawlty Towers was shot in front of a live studio audience. (A real studio audience too – no canned laughter here.) It’s a style of programme which has rather fallen out of fashion in the UK these days; only a few stragglers like Not Going Out and Kate & Koji remain. I will admit to being an unashamed ambassador for what a studio audience can bring to comedy. For a start, an audience forces your sitcom to actually be funny; you can’t get away with inducing a wry, silent smile. It also helps the timing of the performances – actors can react to the room, rather than a vacuum. Obviously you don’t want every TV show to have an audience; different material suits different production methods. But for certain kinds of comedy, nothing quite matches the atmosphere of an audience sitcom. It brings the whole thing alive.

I don’t think there’s anything particularly controversial in the above. But to some people, it really seems to be. And it’s when you hear the arguments against doing any sitcom in front of an audience that I begin to get infuriated. One persistent canard is the idea that “I don’t need to be told when to laugh”. Which is not in any way the point of a show having a studio audience, and starts to reveal the said person’s own neuroses in a manner which would make Basil Fawlty proud. To decry the presence of audience laughter in a sitcom under any circumstances seems to me to be a profoundly anti-creative thing to do. It’s the same as criticising all musicals because “people don’t just suddenly start singing in real life”. To demand some petty interpretation of realism just because a viewer has no imagination doesn’t seem to me to be the best way of creating good television.

Fawlty Towers demands an audience for all kinds of reasons, not least because there are huge laugh lines which utterly demand a reaction. But here’s one big reason why I feel a studio audience is so important to the show: because humiliating Basil is so much more satisfying when it’s done in public. The sound of hundreds of people laughing at his ludicrousness is important. We can understand Basil, we even can feel sorry for Basil, but crucially: it’s important to laugh at Basil too. After all, do you want to end up like him? The studio audience is a vital part of his ritual humiliation.

That’s why Fawlty Towers stands as a template of how to do a mainstream sitcom today. People often focus on the show’s ludicrously complicated plots, and yes, they’re fantastic, immaculately constructed things. But a large part of the joy of the show is poking a character who deserves to be poked, over and over again, while he continues to embarrass himself. That was valid comedy in 1975, and it’s equally as valid in 2022. Giving a kicking to one of the less attractive parts of being British is surely what our comedy is designed for.

People are obsessed with the idea that old comedy easily becomes “dated”. I usually find this to be at best an overstated phenomenon. Humans don’t change that quickly, and some things are eternal. Fawlty Towers is essentially about an incompetent, angry sycophant. It’s not like that breed of human has disappeared in the last few decades.

And they still need to be made fun of. Perhaps more than ever.

Read more about...

bbc100, fawlty towers