Previously on Dirty Feed, I took a look at the differences between the script taken into rehearsals for Dennis Potter’s 1965 play Stand Up, Nigel Barton, and what was finally broadcast. (Please read that first piece if you haven’t already; it contains a lot of background necessary for understanding this one.) This time, we take a look at Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton, broadcast the following week on the 15th December 1965. Fittingly enough, Vote – Potter’s cry of desperation about the state of politics – got bogged down in behind-the-scenes politics of its own, and ended up with a rather chequered production history. So first of all, it’s important to define what this article isn’t.

Unlike the relative peacefulness of Stand Up‘s production, Vote not only had a major rewrite, but that major rewrite was after the whole thing had been shot. Potter details in his introduction to the Penguin scriptbook The Nigel Barton Plays that the play was originally ready for broadcast on the 23rd June 1965, but that executives started to get cold feet and pulled the play seven hours before transmission.

Between June and the play’s eventual December broadcast, several scenes were rewritten and reshot. Needless to say, Potter wasn’t very happy about it.

“The result disfigures the play in a few important ways. Firstly, some of the savagery of Jack Hay’s cynicism had to be muted. It was argued that, in the original, the agent was ‘almost psychotic’. After much edgy negotiation, I was able to settle for what is now in the text – but I hope it will be clear […] that any further diminution in the bite or the fury of the part would have ruined the play.”

The crucial bit for us in terms of analysing the changes made to the text is the following:

“Like the new Jack Hay I, too, have my own ‘private grief’ and nothing will now induce me to publish the original Vote Vote Vote for Nigel Barton (nor the original of my Cinderella). These published texts are to be related to what was actually shown on the screen.”

Which means we have a somewhat different situation here compared to that with Stand Up, Nigel Barton. There, we could be certain that the text as published in The Nigel Barton Plays was what was taken into the rehearsal rooms. Here, Potter admits that the script published for Vote is not his original intention. These certainly aren’t transcripts, as there are plenty of differences between this script and what made it onto the screen – so they are presumably an amalgamation of his original script, and the specific scenes featuring Jack Hay which he delivered as rewrites.

So, what this article can’t detail is Potter’s original vision. You don’t get the old, even more twisted Jack Hay here, I’m afraid. We only have what is published in The Nigel Barton Plays to go on. We will, however, analyse the sections of the script which Potter admits were rewritten… and in at least a couple of instances, we can tell that the enforced rewrite on his character has entirely been ignored when it came to actually shooting the thing.

Enough background. Let’s get going. Material from the book is styled like this, and dialogue from the show as broadcast is styled like this. Note that I haven’t detailed every single change in wording between the script and the screen – only the stuff where there seemed to be an interesting point to make, or where there have been clear censorship issues.

A short discursion about titles

A question. Exactly what shall we call this play?

The opening title card calls it Vote, Vote, Vote, for Nigel Barton. The closing titles call it Vote Vote Vote for Nigel Barton. The Radio Times calls it Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton. The book The Nigel Barton Plays calls it Vote Vote Vote for Nigel Barton. The DVD cover calls it Vote, Vote, Vote, for Nigel Barton. Finally, the DVD menu calls it Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton or Vote Vote Vote for Nigel Barton depending on which menu you’re on.

Ultimately, if there’s anything my job has taught me, it’s: go with what the Radio Times tells you, even over what you see on-screen. So I’ve called the play Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton, aside from when I’m quoting sections from Potter’s introduction to The Nigel Barton Plays, when I’ve gone with his preferred Vote Vote Vote for Nigel Barton.

Happy? No? Good.

1 • Fox-Hunting Scene (0:00)

1) Potter’s description of the hunt which opens the play is rather minimalist:

The fox panting hard, the bay of hounds, blast of trumpet, thunder of hooves and clods of earth being thrown before the camera. Bleery, bloated, raw-looking faces. Horse and rider jump hedge. Horse falls. A bird sings.

The final play adds shots of various horsey types enjoying wine and the like, which ties in nicely with the kind of person we see during the climax of the play.

2) Most of the dialogue during this opening is identical, but it’s worth noting that the stage direction for the accident simply says:

Small horsey group, slapping their whips, are gathered round a portly figure sprawled under the hedge.

The macabre touch of the scene being seen from the point of view of the dying Harry is nowhere in the script.1

2 • Television News-Room (1:51)

3) The newsreader:

News has just come to hand that Sir Harry Blakerswood, the Conservative M.P. for West Barset and former Minister of Fine Arts has been killed in a hunting accident. [Sadly] His horse has also had to be shot.

The stage direction “Sadly” is ignored by Huw Thomas. Probably for the best – a BBC newsreader wouldn’t say the line like that – but it’s a funny gag on the page.

3 • Barton’s Flat: Night (2:17)

4) Not a cut, just an observation – the first thing out of Barton’s mouth in both the script and final play when he hears about the death of Blakerswood is:

NIGEL: Oh my God!

Which is a little odd, considering how many blasphemous references were cut out of Stand Up, Nigel Barton the previous week. And he’s at it again, seconds later:

NIGEL: Anne, Anne, did you hear that? My God… poor old Blakerswood!

5) Back to normal later in the scene, mind:

NIGEL: Pour me a drink for Christ’s sake.

NIGEL: Pour me a drink, please.

“Christ” as a swearword appears to be verboten across both Stand Up and Vote. (Not for nothing does Potter highlight the word being cut in his introduction to The Nigel Barton Plays.)

6) An interesting performance decision from Keith Barron. From the script:

NIGEL: [gloomily] I can just see myself about a month from now, jawing away at a bunch of stupid old women in a ramshackle village hut. I’ll talk about Vietnam… and they’ll ask me about the smell from the sewage farm on the main Barset Road.

In the final play, Nigel laughs as he says this. Maybe slightly bitterly. But he laughs. A far better decision than the note on the page, I think.

Also of note: the word “hut” in the script here is changed to “hall” in the final version. It perhaps seems slightly bizarre that Potter thought the word “hut” was sensible in the first place here: the mention of Vietnam makes you briefly wonder whether Nigel is talking about over there when he starts banging on about huts.

7) When Jack Hay rings, there’s the following stage direction:

There is an incomprehensible gabble from the phone. NIGEL holds it away from him with a wry expression.

In the final programme, we hear Jack quite clearly, which is probably for the best. Comedy telephone noises wouldn’t quite suit the mood of the play.

4 • Telephone in Office: Night (5:31)

8) When we first see Jack Hay, the scene is extended slightly on-screen:

HAY: Yes, yes Nigel, I thought you might feel a bit peeved.

NIGEL: I’m not peeved, Jack.

HAY: But I think you’d be a fool to turn it down. It could be your big chance.

NIGEL: Big chance, do you mean it?

HAY: But of course I mean it.

NIGEL: I don’t know, Jack. Look, we’ve been through this before.

HAY: Yes, but a by-election’s very different, old mate. Don’t you see?

NIGEL: No, I don’t.

HAY: Well, you’ve got big-name speakers. Big issues.

NIGEL: Really?

HAY: Yeah. The press. TV cameras.

NIGEL: Oh?

HAY: Lots of public interest. [Jack winks at the camera.] Excited audiences.

[Puts phone down and winks.]

Perhaps Potter was trying to be a little too economical on the page.

Also note that Jack is supposed to put the phone down at the end of this scene in the script – he doesn’t in the final play, indicating this is the start of a long conversation with Nigel, which works far better.

5 • Village Hall: Night (5:56)

9) According to the stage directions, Nigel is supposed to drag nervously on a cigarette in this scene. In the final version, no cigarettes are to be seen.

10) Right, let’s have a discussion about exactly when this play is set. The date of the previous Labour Women’s Group meeting is given in dialogue here as the 5th March 1965; the mention of raffle “this week” indicates this meeting takes place on the 12th March 1965. Now, let’s turn to Potter’s introduction to The Nigel Barton Plays again:

“Vote Vote Vote for Nigel Barton was first telerecorded in March 1965 for an intended transmission the following month. A technical flaw spoilt every other reel in the film so, after re-shooting, the play was once more ready for screening on Wednesday, 23rd June. But by that time a few highly-charged whispers about the ‘dangerous’ nature of the play had begun to drift round and round the rubbery, anonymous and appropriately circular corridors of the hideous new B.B.C. Television Centre. One by one, B.B.C. executives were called in to see the telerecording and were seen to emerge shaking their heads like nervous marionettes. And seven hours before it was due to go out on the air, the B.B.C. announced that the play was being withdrawn. It was, they said, ‘not ready’ for transmission.”

In other words: this scene was originally supposed to be set just a month before the television audience saw the play in April 1965. Instead, due to the reshoots, it was shown a full nine months later.

Now, let’s leap ahead to the very final scene in the play:

NIGEL: Ladies and Gentlemen, polling day tomorrow… Tomorrow you have a chance to use your vote. It is perhaps the greatest privilege you possess. I ask you to use it.

This is The Wednesday Play, so the device of Nigel identifying “tomorrow” as polling day would not be lost on the audience whichever particular Wednesday it was transmitted. But the intended April airdate means we were clearly meant to see the Labour Women’s Group Meeting in March as the start of his election campaign… and Nigel’s pleas to vote “tomorrow” are the cumulation of it.

Sadly, transmission being put back until December ruins the immediacy of this timeline – instead of seeing Barton in the here and now as intended, the audience saw what he was up to nine months ago instead. This is the kind of thing which is utterly invisible when viewing the show on DVD… but would have made a real difference on its first transmission.

11) When the minutes of the previous meeting are being read out, the stage direction tells us that “NIGEL exchanges agonised, hostile glances with his agent”. Barron plays the moment instead as though he’s struggling not to laugh, which feels more suitable at this point in the play. We get more than enough of the agonised, hostile Nigel later on.

12) When Nigel is about to drink flower water:

MRS THOMPSON: It was used to bring them bloody flowers.

MRS THOMPSON: What them there flowers come in.

It seems a little odd that ‘bloody’ would be removed here – it was liberally used in Stand Up. (And, indeed, has already been used in this play – in the opening film sequence with the horse accident.)

13) Nigel’s mistake:

NIGEL: I thought for a moment there that my fly buttons were undone.

NIGEL: I thought for a minute there that my flies were undone.

“Flies” is so, so much funnier than “fly buttons”, which has entirely the wrong comedic rhythm, and is also too polite. The broadcast version is much better here.

6 • Village Hall: Night (9:46)

14) As Nigel and Jack reflect on the evening’s events, our ongoing war on the word “bloody” removed a nice bit of alliteration:

NIGEL: And Miss Birrell with her bloody bird book.

NIGEL: And Miss Birrell and her bird book.

15) And when Nigel and Jack contemplate Nye Bevan:

NIGEL: Well, you should have heard him at that Suez demonstration in Trafalgar Square. He was bloody marvellous.

NIGEL: You should have heard him at the Suez demonstration in Trafalgar Square. He was marvellous.

Anyone spotting a pattern here?

7 • Nigel’s Flat: Night (12:36)

16) Back at the flat:

NIGEL: Just a harmless bunch of broken-down old women who prefer to raffle jam sponges than discuss the Bank Rate.

NIGEL: Just a bunch of stupid old women who prefer to raffle jam sponges than discuss the Bank Rate.

Nigel comes across slightly harsher here in the final play than in the original script.

17) Right, as the evidence mounts, it’s probably time we addressed this properly:

NIGEL: Ho bloody ho ho!

NIGEL: Ho jolly ho hum.

This is really peculiar. Aside from the opening film sequence, there seems to be a determined effort to expunge the word “bloody” from the script. And yet the word was used all the time in Stand Up, Nigel Barton, broadcast just the previous week. For Vote to suddenly get squeamish about the word is just… well, bloody weird.

18) Speaking of weird:

NIGEL: Walked up and down the pit bottom he did with his mates, debating whether or not the Economist didn’t better reflect the current situation.

NIGEL: Walked up and down the pit bottom he did with his butties, debating whether or not the Economist didn’t better reflect the current situation.

So, after Stand Up removed every single instance of the miner slang “butties” from the script… the word is added between the script and the final play here! What the hell?

19) When Anne has the temerity to suggest Nigel had “the advantage” of growing up in a working class home:

NIGEL: You silly bloody cow.

NIGEL: You silly flaming cow.

The censorship of the word “bloody” is even more of a shame here than usual: Nigel calls Jill a “silly bloody cow” in Stand Up, and the loss of the parallel with how Nigel talks to Anne here is unfortunate.

8 • Jack Hay’s Office: Day (15:20)

20) The stage directions at the start of this scene state Nigel’s placard should read “Nigel Barton speaking for Labour”. We’ve already seen the posters in the village hall, but this has been changed to “Let’s GO with LABOUR / Vote Nigel Barton”.

(Man, the money I’d pay for one of those posters. Even a replica.)

21) When Jack picks up the phone, the script doesn’t give the priest’s name, but the final play names the caller as Father O’Malley. It also pulls the same trick as we saw earlier: we can actually hear the priest’s responses in this scene over the other end of the phone, none of which is in the script.

In the original script, the pair arrange the meeting for the rather inaccurate time of “Monday”. Clearly they realised that doesn’t actually make a lick of sense once they got into rehearsal, as extra dialogue in the final programme clarifies that the meeting is for 12 o’clock!

22) After Jack Hay gets off the phone:

HAY: God almighty. Democracy is so bloody complicated.

HAY: Democracy is so complicated.

Two bits of censorship for the price of one!

23) Oh-ho-ho-ho-ho, what’s all this? When Jack is listing the various groups they need to send a friendly note to, there’s the following change:

HAY: …the Keep Television Clean group…

HAY: …the Keep Bread Pure group…

It’s difficult not to suspect this was just a matter of not prodding the beast for the sake of it, but this change seems a particular shame to me.

24) More blasphemy gone:

HAY: Now, where the hell was I?

HAY: Now, where the heck was I?

9 • Public Hall: Night (17:37)

26) None of the public’s interjections during the meeting are scripted, so this is presumably a scene which much benefitted from the rehearsal process. Which means the script is missing the following delightful line:

NIGEL: And who, I ask you, who is most likely to need false teeth and spectacles?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You!

27) Interestingly enough, Jack’s reply to Anne – “About bloody time too” – has the bloody left intact in the final play, which the first instance of the word being used in a studio sequence. Y’know, just in case we were trying to nail down some kind of reasoning or pattern or something.

28) Though in the same conversation, the following line was cut from the final play:

HAY: Facts and figures bore the arse off people!

Shades of the line “arse from his elbow” being cut from Stand Up, I think.

29) Towards the end of Nigel’s speech, the stage direction notes “He begins to get shrill.” Barron wisely reigns things in a little here and doesn’t follow this instruction.

10 • Nigel’s Flat: Night (22:56)

30) In both the script and the final version, Nigel says “This is a hell of a period, Anne”. So, Nigel gets to keep his use of the word “hell”, but not Jack Hay earlier. Perhaps they were under some kind of quota, and decided to keep the word where it counts?

31) Oh look, Nigel’s arguing with Anne again:

NIGEL: Of course you aren’t. Nothing so bloody human!

NIGEL: Of course you aren’t. Nothing so human!

32) And again:

NIGEL: My God! Listen to the condescension!

NIGEL: Listen to the condescension!

33) And again:

NIGEL: Don’t sulk, for Christ’s sake.

NIGEL: Now, don’t sulk.

34) Directly after that, some additional dialogue in the final play which isn’t in the script:

NIGEL: You know very well what I mean.

ANNE: That I’m eaten up with guilt? It’s not true.

NIGEL: Well why do we snipe at each other like this?

ANNE: Because you’re the guilty one, or ought to be.

NIGEL: Here we go again!

Was someone worried that we needed an direct explanation of why Nigel and Anne keep fighting? It feels a little superfluous.

35) The script notes that Nigel is supposed to sound “scornful” when musing about sherry. Keith Barron shows no trace of that in his performance; indeed, it’s like a wistful reminiscence.

36) In the same speech, where Nigel talks about growing up:

NIGEL: …books being called muddles…

NIGEL: …books being called rubbish…

This is exactly the same change as made at the end of Stand Up, Nigel Barton – in his television interview, the script has Nigel calling books “muddles”, and it’s changed to “rubbish” in the final version. This change thus keeps the intended parallel, thankfully.

37) Yes, OK, I’m banging away at the same point:

NIGEL: …Coco the bloody clown!

NIGEL: …Coco the clown!

38) This is highly amusing:

ANNE: It’s been well documented in Jackson and Marden’s book, Education and the Working Class.

ANNE: It’s been well documented in Jackson and Marsden’s book, Education and the Working Classes.

And the correct book is…

11 • Street: Day (28:32)

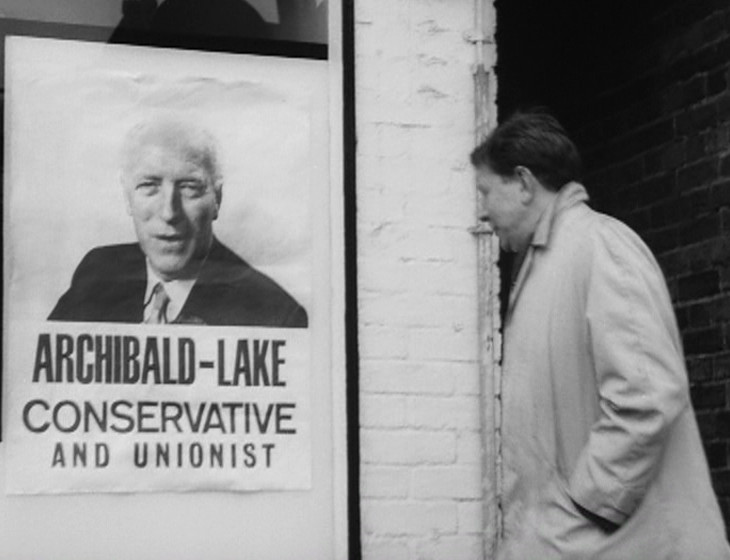

39) We get a little more scene-setting in the final play than in the original script here: we actually see a poster of Conservative candidate Archibald-Lake, which is never mentioned in the script.

40) The pedestrian who has a word with Nigel was originally a little stronger in his insult:

PEDESTRIAN: You’re talking a load of bloody nonsense!

PEDESTRIAN: You’re talking a load of rubbish.

It feels like a shame this was changed; something a little stronger directed towards Nigel would have sold the moment better here. Perhaps he should have called him a cunt.

41) An odd little stage direction, which isn’t paid attention to in the final play:

NIGEL [amplified]: Remember, when the time comes, Let’s Go With Labour…

PEDESTRIAN: [shouts after the van, waving his fist] And we’ll all get done!

This all feels a little over-the-top, and was wisely ignored when it came to the actual shooting. In fact, there’s a pattern in Vote of Dennis Potter suggesting acting choices, which are then ignored in the actual production – and most of these directions seem a little too broad for the tone of the play.

12 • Interior of Van (29:30)

42) The script notes that the van is “parked on the grass verge near a group of council houses”. In the final play, Jack is still driving as him and Nigel have the opening conversation, which is a little more dynamic.

43) Jack’s reference to “bloody intellectuals” while out canvassing is left intact in the final play. It’s clear at this point that the word wasn’t verboten, but they were worried how many times it was used, and decided to cut back.

Additional • Horse Riding Club (33:27)

44) Scenes 13 and 14 on the doorsteps go pretty much as scripted. But here we come to a bit of an oddity. The final broadcast version of the play has an entire extra scene, not in the original script at all, with Nigel canvassing at a horse riding club:

NIGEL: Do the Tories think we’re going to perpetuate their 13 long, miserable years of misrule? I ask you to remember my previous remarks about their ridiculous mismanagement at their so-called Ministry of Agriculture. Now, this should be a subject close to all of you listening to me here today. It concerns you. It will concern you on polling day. So remember, when the time comes, let’s go with Labour and we’ll get things done. Polling day is next week. Remember – vote Labour and we’ll get things done.

A horse whinnies.

This scene adds a little bit of colour to proceedings, but there doesn’t seem to be a huge amount of point to it. Indeed, keeping the rule-of-three when it comes to canvassing around the houses would seem to be more effective to me.

16 • Road: Day (35:32)

45) The scene with Mrs. Phillips on the doorstep is pretty much as scripted. We then go onto Jack’s big speech where he lets the mask slip:

HAY: My old man used to keep me from school on Empire Day so I wouldn’t have to wave those little blood-coloured flags.

HAY: My old man used to keep us away from school on Empire Days, so we wouldn’t have to wave one of those little Union Jacks.

You have to wonder whether the association of violence with the flag was deemed unacceptable.

Scene 17 is the Movietone footage featuring Oswald Mosley, which has something extremely interesting about it. In fact, it’s so interesting that I’ll defer discussion of the scene for a later article. So, let’s go straight on to:

18 • Small Hall: Night (39:59)

46) Interestingly enough, Mrs Morris’s lines are left intact, despite containing a grand total of four uses of “bloody” in four lines:

MRS MORRIS: Blow the bloody bugle!

Bang the bloody drum!

Blast the bloody bourgeoisie!

To bloody kingdom-come!

Although being a quote, the lines would have been impossible to censor without removing them entirely. I don’t think even the BBC in 1965 would have gone with “Blow the ruddy bugle”.

47) This scene features one of the rewrites of the character of Jack Hay which the BBC forced on Potter. As he says in his introduction to The Nigel Barton Plays:

“Similarly in Scene 18, at the meeting of the General Management Committee, Hay once more has to be identified as someone who ‘must have been a very great idealist once upon a time. Nobody could dare to be as cynical as you pretend to be without knowing what it is to believe and to hope.’ There then follows a stage direction which genuinely fills me with shame. ‘Hay rolls his eyes, but not convincingly. He is moved. Sob, sob.”

The scene as broadcast does indeed include the dialogue identifying Jack as a “great idealist”. What is fascinating though, is that the stage direction Potter abhors so much, of Hay unconvincingly rolling his eyes, is roundly ignored!

Even amid all the chaos and annoyance of the reshoots… the show is pulling back from the more extreme demands which were requested. What’s perhaps even more fascinating is that in highlighting it, Potter seems to be unaware that this particular stage direction was ignored in the final production.

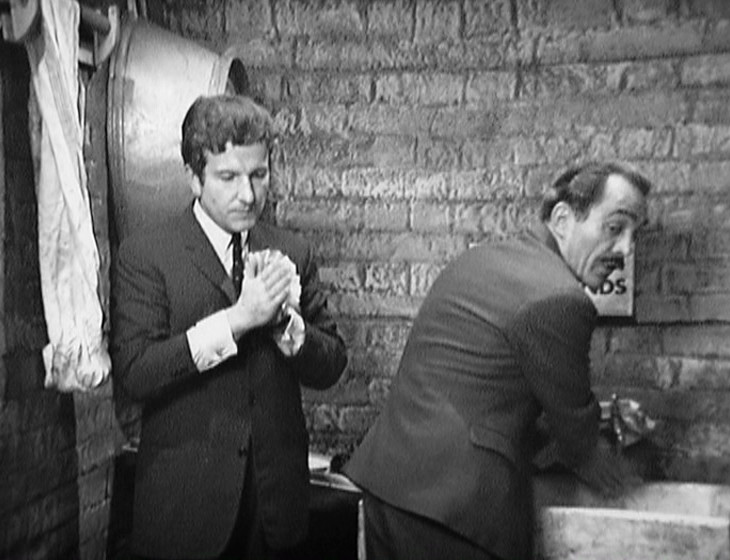

19 • Washroom: Night (43:54)

48) A rather interesting name change:

HAY: I reckon that with any luck and a bit of the old sunshine and Sir Alec on the telly on the eve of the poll, we shall chop the Tory majority in half.

HAY: I reckon that with any luck, a bit of the old sunshine, and Quentin Hogg on the telly on the eve of poll, and we’ll chop the Tory majority in half.

Did they think Alec Douglas-Home would make too much of a fuss if his name was used here?

49) When Nigel is offered the list of people recently bereaved in the constituency, Nigel’s “Oh my God” is left intact. In general, despite some removals, Vote seems to be more comfortable with blasphemous references than Stand Up.

50) Another stage direction for Jack Hay which is wisely entirely ignored:

HAY: I can now see that this harmless little request was the last straw so far as Nigel was concerned. It seemed to sting him in the forehead, if you follow me. I’ll bet he brooded over it all night long. [This last sentence is said sympathetically, as if HAY, too, has brooded. The shrug which follows shakes him back to normal.]

Again, this is clearly one of Potter’s aforementioned rewrites to make Jack Hay more sympathetic – and again, it’s especially intriguing that it was ignored. The damage done to the play by the rewrites that Potter bemoans really has been limited by the final performance ignoring some of this stuff.

20 • Nigel’s Flat: Night (45:45)

51) After Anne calls Nigel impotent, in the script she merely says “Oh darling!” As broadcast, she says “Oh darling, I’m sorry!”, and goes to hug him – an action nowhere in the script, and makes her seem a lot more sympathetic.

52) The end of the scene is extensively revised:

ANNE: I’m going to be. [She turns at the door, venomously.] Oh, by the way, don’t forget your rosette in the morning.

NIGEL: [trying to make up] It makes me feel like a prize bull at an Agricultural Show. Moooooooo!ANNE: Yes, you’ve got a point there. Still, it goes well with a prissy cow. Don’t it, then?

[They kiss.]

NIGEL: Just a minute…

ANNE: What are you groping for?

NIGEL: Just a minute…

ANNE: You’re tickling…

NIGEL: Oh, heck.

ANNE: Eee, what hot, passionate breath. Right down my…[The camera pans away. They continue giggling.]

ANNE: Just as well we’ve been married for five years, dear…

I mean, at this point, it’s just nice to see a scene where Nigel doesn’t call Anne a cunt or something. But this is certainly the most affectionate we ever see Nigel and Anne together; the fact that this wasn’t in the script originally is intriguing, as it puts their relationship in a very different light.

It would be remiss of me to point out, however, that the addition of this dialogue adds a continuity error. The scene earlier at the Labour Women’s Group meeting gives the year of events as 1965; this scene therefore indicates that Nigel and Anne got married in 1960. But the Proctor’s Office scene in Stand Up, Nigel Barton identifies the year as 1962, meaning that apparently Nigel and Anne had been married for two years while Nigel was fooling around with Jill.

This does, of course, invalidate both plays entirely.

There’s no significant changes in the next three scenes. We then come to the climax of the play:

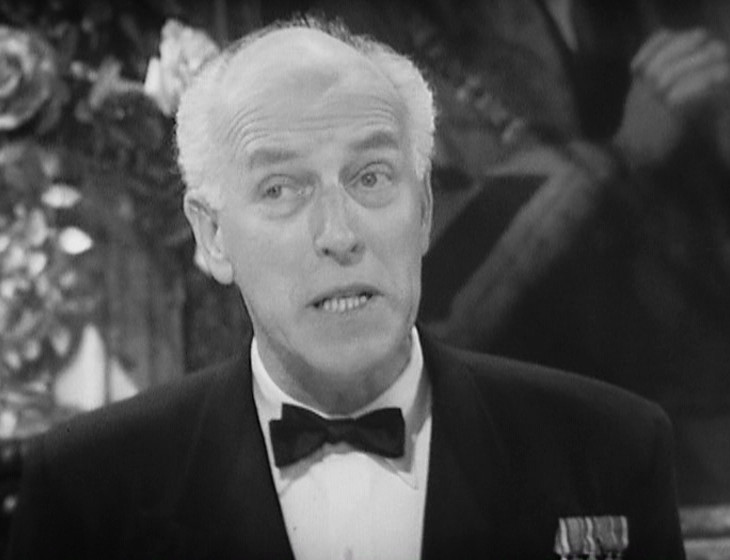

24 • Council Dinner: Night (55:47)

53) Archibald-Lake is described in this scene in the script as having half-lens spectacles, and peers over them”, which are nowhere to be found in the final play.

54) Some rewording when Archibald-Lake talks about his opponents:

ARCHIBALD-LAKE: I must admit in all honesty that they have all seemed to me to be honest, honourable, well-meaning and reasonably patriotic young men.

ARCHIBALD-LAKE: I must admit in all honesty that he seems to me to be an honest, honourable, well-meaning and reasonably patriotic young man.

This is an excellent change: making Archibald-Lake’s speech speech more personal to Nigel makes it much more dramatic.

55) Cut, after Archibald-Lake bangs on about some guff to do with the National Anthem:

NIGEL: [between his teeth]: For God’s sake!

ANNE: [alarmed] Shhh! [She is alarmed at the thought that NIGEL might be about to take her advice to ‘be honest’. NIGEL looks at her with malicious amusement.]

Probably a wise cut; we don’t want to get Nigel too riled too early. We’ve got a long scene ahead.

56) Shortly after, there’s an extra cutaway present in the broadcast version but not in the script:

REPORTER: Who’d be a reporter?

A useful addition: this brings in the idea of the event being reported on earlier than it does in the script, which is useful for the denouement.

57) A slight change from Jack:

HAY: Be polite, I said. Be polite!

HAY: ‘I’ll be smooth’, he said. Smooth!

It’s worth noting that Hay never actually told Nigel to be polite in the previous scene – but Nigel did promise to be smooth. A good, logical change.

58) Again, another addition to the broadcast version, as Archibald-Lake witters on, we get a close-up of Nigel, as he remembers…

HARRISON: [voiceover] I only want me leg!

This is one of the biggest changes in the whole play in sheer dramatic terms – there is no such flashback at all in the original script. This addition really twists the knife.

59) An interesting change: in the script, the toast is to “the Council and Citizens of Barset”. In the broadcast version, it is to “the mayor and mayoress and councillors of Barset”. In the final play, ordinary citizens aren’t deemed worth of being even mentioned, which seems appropriate.

60) Jack’s pleading was originally a little more baroque:

HAY: Please God let him lose his voice; Please God let one of the trout bones stick in his throat. Please God, make him choke.

HAY: God, please make him choke.

The opportunity wasn’t taken here to remove the bit of mild blasphemy – use of “God” seems altogether more accepted in Vote than it did in Stand Up.

61) During Nigel’s two-fingered salute to Archibald-Lake, the script gives us “Music – Colonel Bogey”. No music at all features in this scene in the final play, although perhaps this suggestion inspired the march used over the end credits.

62) Also during this sequence, we’re supposed to see the “flash lights of press cameras”. What isn’t scripted is the brilliant animation of the moment into the front page – the action was merely supposed to freeze.

25 • Hay’s Office: Day (1:11:08)

63) An extra line, present in the script but not in the broadcast:

HAY: Anybody’d think the fool was at the Labour Party Conference. I’ve never been so humiliated in my life.

An excellent cut – the extra line dulls the joke.

26 • Barton’s Flat: Day (1:11:14)

64) A bit of an odd stage direction – early on, as Anne is enthusing about Nigel’s performance at the dinner, we’re told that “Nigel looks at Anne, beginning to hate”. It’s far too early for that – she hasn’t even begun to talk about weaponising his political outrage yet – and Keith Barron wisely takes no notice of it.

27 • Hay’s Office: Day (1:13:23)

65) When Jack is talking directly to camera, there’s one additional line in the final play absent from the script which I think has a huge impact:

HAY: You may despise me, but don’t blame me – because it’s all your fault. There’s a lot of good in him. A lot of good. But you’d never vote for a Nigel Barton in a million years.

Directly telling the audience that it’s all their fault is one of the most powerful lines in the whole speech – and it’s missing from the script entirely.

66) And finally, when Nigel hits the poster and does his famous final speech, the idea of the camera flicking between the Nigel of the poster and Nigel himself is entirely absent from the script. Perhaps this isn’t surprising, it being a directorial flourish – but it’s worth noting, if only because the sense of Nigel’s duality doesn’t quite come across in the script in the forceful way it does in the final production.

* * *

So, what have we discovered in our trip through the two Nigel Barton plays, beyond the fact that throwing in additional dialogue at rehearsal stage can cause you a nasty continuity error if you’re not careful?

For me, what I find most interesting is that despite these two plays being broadcast just a week apart, different standards seem to have been applied to them when it comes to censoring the language. And while there are exceptions to the rule, in general it seems Stand Up was less concerned about the use of the word “bloody”, and more concerned about blasphemy; Vote has it exactly the other way around.

Now, I wasn’t quite expecting the BBC to treat the censorship of these plays using a great big rule book, ticking off exactly what could be said and could not. But I still find the differences here intriguing; not only were the plays broadcast just a week apart and had the same writer, but they even share the same director. And whilst I don’t quite want to go as far as to call some of the changes entirely arbitrary, it’s certainly difficult to take many of them particularly seriously when the plays are compared side-by-side.

And that’s where I expected to leave this overly-lengthy analysis for now. However, there remains one last bit of business to take care of. Remember that Movietone footage of Oswald Mosley speaking on unemployment, where I said I’d made a rather interesting discovery?

Next time, in the third and final part of this series, we take a look at how Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton – perhaps accidentally – played a role in preserving a genuine part of history.

Or here’s an odd thought, which is so odd I’m relegating it to a footnote. After the POV shot, the very next thing we see is a zoom-in on the eyes of the injured horse. Is the whole scene taking place from the horse’s point of view? ↩

One comment

Jack on 18 April 2018 @ 12pm

Everyone else is wrong. Clearly the correct title is:

Vote, Vote Vote! for Nigel, Barton.

Comments on this post are now closed.