The Brittas Empire: “Curse of the Tiger Women”

The Brittas Empire: “Curse of the Tiger Women”

Written by: Ian Davidson and Peter Vincent

Produced by: Mike Stephens

Directed by: Christine Gernon

TX: 24th February 1997

This is the story of one of my least favourite endings to a sitcom ever. But to figure out what went wrong, we need to skip backwards three years…

In 1994, The Brittas Empire had a pretty incredible run. No less than seventeen episodes were broadcast1, across two series – and amongst those seventeen were some of the show’s very best episodes. Examples include “High Noon”, where the leisure centre is blown up on a sitcom budget (and largely convincingly, to boot); the audacious “The Last Day”, where they kill Brittas off, send him to heaven, and then resurrect him during his burial; and “Not A Good Day”, where… they chain Sebastian Coe to a railing and watch him suffer for half an hour.

What happened next is uncertain. The generally accepted sequence of events is that writers Richard Fegen and Andrew Norriss intended Series 5 to be the last series, the BBC recommissioned the show due to good viewing figures, Fegen/Norriss weren’t interested in returning, and so the BBC hired in new writers and told them to get working. I can’t find any interview which explicitly supports this story, but certainly Series 5 feels like the series was building to an deliberate conclusion. Every character gets their exit, with everyone given a chance of happiness: Laura moving to America to have a family; Carole becoming a governess; Julie marrying into a rich family; Linda accepted into Theological College; Gavin about to become manager of the centre, with Tim cheating his way into being his deputy… and Brittas off to Brussels, if he can recover from being dead. If this wasn’t supposed to be the final series, it’s doing a bloody good impersonation of one.

But no matter if the show had reached a natural end: there was work to be done. So the last two series, whilst still produced by Mike Stephens (who had been there from the very beginning), were by other writers: Ian Davidson and Peter Vincent, Tony Millan and Mike Walling, Terry Kyan, and Paul Smith. As writing assignments go, it has to be said this was a pretty thankless task. For a start, The Brittas Empire always had a very specific voice that is hard to suddenly get other writers to imitate – the programme title never sold how unusual the programme really was. (Though it did help them slip an awful lot of things under the radar.) Secondly, Series 5 was all about sending off the characters to their own happy endings – all that had to be cancelled, inevitably rather awkwardly. Thirdly, Julia St. John had decided to leave the series – and it’s difficult to overstate exactly how crucial a character Laura was. The moments of attraction between her and Brittas were some of the most emotionally touching in the entire series, but the character also manages the seemingly impossible: the “sensible woman” character amongst all the chaos. Usually that character is a waste of everybody’s time – but here, it’s done right. (A wry smile and a wink will get you further than relentless exasperation.)

Worst of all, we come back to that final episode of Series 5. In an extraordinary sequence, Brittas gets squashed by a falling water tank (in some of the best effects work the series ever did), whilst saving Carole’s life. We see him go up to heaven, just scraping past the gates (“115 separate acts of manslaughter… cause of four people committing suicide… and 23 driven clinically insane…”) – and then being sent back down to earth for being an annoying little shit (“You take my word for it Peter, 2000 years is not too old to start playing seven-a-side!”) Meanwhile, the scenes on earth are played absolutely real – this is not treated as a comedy death. Our characters are genuinely in mourning. All until the burial… where we hear a knocking from the coffin, as Brittas awakes. It’s an amazing sequence – one of the most audacious in sitcom history – but it partly works because it has a sense of finality to it. Where the hell would any series actually go from there?

To be fair, they make a pretty decent stab at it. The emotional beats aren’t as good, the lines aren’t as sharp, and the plots aren’t half as well constructed – always the biggest strength of Fegen and Norriss – but those last two series perhaps work better than they could have done. Sure, the Laura replacement Penny is dreadful (and dropped for the final series), and the back-tracking on the fates of the characters is inevitably disappointing (with Carole’s being the worst) – but at least they bother to try, rather than just ignoring everybody’s fates and resetting things back to normal with no explanation. (The reason for Brittas failing the medical for Brussels is especially amusing: “He was dead!”) It’s also worth noting that the first episode of Series 6 even takes the unresolved plot point of an bomb from the penultimate episode of the previous series, and resolves it… in the usual Brittas manner. (Yes, a big explosion.) This shows a certain kind of care which is not always taken when a show is handed over to other writers.

Most crucially, however, the writers understand that Brittas has, as Mark Lewisohn put it, an “unusual obsession with death and danger”. Certainly, the gloriously tasteless vision of a class of schoolkids being electrocuted whilst roasted peace doves fall from on high is something well worth broadcasting at 8:30pm on BBC1… even if the episode in question had to be postponed due to Dunblane. Whatever the faults of the last two series, taming it down into a “normal” sitcom is not one of them. Unfortunately, it’s this last point which leads to the biggest mistake made in those last two series… and here, we drag it back to that final episode: “Curse of the Tiger Women”.2

Because how do you end a show like Brittas? Series 4 ends with blowing up the leisure centre; Series 5 ends with the aforementioned death and resurrection of the lead character. It’s easy to see how Fegen and Norriss might have decided further series really weren’t such a good idea. To their credit, the doomed writers Ian Davidson and Peter Vincent realise that Brittas can’t have a normal ending, and so they decide to try for something memorable. Unfortunately, the idea they go for is possibly the worst they could have come up with.

After an episode full of the usual: a gypsy curse, a build-up of marsh gas, Noah’s – sorry, Colin’s Ark, yet another scene full of dead birds dropping from the sky, and a ludicrous flying goose prop, we fade through to Brittas waking up on a train. Colin is the ticket inspector; Julie is in charge of refreshments, Linda is a nun… all the regular cast are merely passengers. Brittas is on the way to his interview for the job of manager at Whitbury Newtown Leisure Centre… and everything was all a dream. Not just that final episode. Not even just the final series. The whole show, from the very first episode. And all so they can do this line:

BRITTAS: I want the job, Helen, because… because… I have a dream.

Yes, yes, ho fucking ho. From the very first episode, we’ve been hearing about Gordon’s metaphorical dream; the final episode reveals he’s been having an actual one. How very clever.

The fundamental problem with this is obvious, and it doesn’t take a great deal of analysis. For all that Brittas is an atypical show full of death and danger and the odd maiming, like any sitcom it’s all about the characters. Hell, that final episode seems to go out of its way to understand this, by finally resolving the long-standing plotline about the real father of Carole’s children… and then it just pisses it all away. None of the series happened. All our investment in the characters over the past seven series was all pointless, because it wasn’t real. I’m rarely someone who will just decide something in a show didn’t happen – but I make an exception for this one. Despite it being easy to understand what would have caused the writers to do it, it’s difficult to think of a more diabolical way to end the programme.

And that is the story of how Ian Davidson and Peter Vincent wrote one of my least favourite dream sequences of all time.

Sorry!: “Curse of the Mummy”

Sorry!: “Curse of the Mummy”

Written by: Ian Davidson and Peter Vincent

Produced and Directed by: David Askey

TX: 16th April 1981

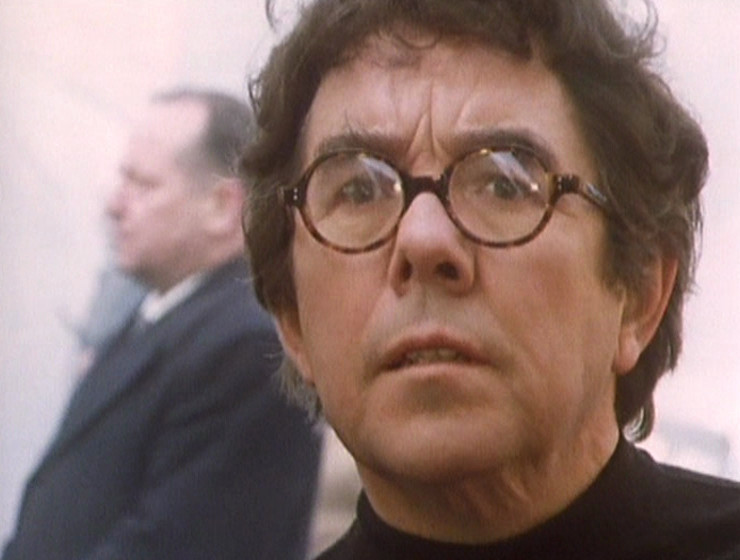

Sorry! is the tragic tale of Timothy Lumsden, trapped in the family home, practically married to his mother… all wrapped up in the guise of BBC light entertainment. As such, it’s one of my favourite kinds of television – the superficially frothy audience sitcom… with a darker undercurrent not too far from the surface. Even the title sequence – at first glance an inappropriate LE neon nightmare – is strangely apposite on reflection. Just as the music for Ever Decreasing Circles reflects Martin’s swirling insanity, the music for Sorry! – round and round, never-ending – reflects how trapped Timothy is… something the repetitious title sequence reinforces.

I keep wanting to call the series underrated, but perhaps that isn’t the right word when it ran for seven series throughout much of the 80s in a primetime slot on BBC1. I would, however, argue the show deserves to be remembered rather more fondly than it seems to be. But then, it probably is… by people who have better things to do than sit here writing silly articles about it online. Still, the oft-repeated mantra “sitcom works best when the characters are trapped” – one of the few cliches people spout about sitcom which is actually true – has rarely been more applicable, unless your characters are locked up in prison or sent into the far reaches of deep space.

That’s not to say that a lot of episodes don’t share a formula3. Timothy starts the episode trapped, Timothy gets a chance of happiness, Timothy’s mother ruins it, Timothy ends the episode still trapped. “Curse of the Mummy”, the final episode of the first series, is a fairly typical episode in that regard. As it’s our first glimpse of his sister Muriel4, the plot is even simpler than usual: she comes to visit, tries to persuade Timothy to leave the family home and come to London with her, and he completely and abjectly fails to do so.

The interesting bit, though, is how he fails. We all know Timothy won’t be leaving his mother this time round; destroying the whole setup of the show at the end of the first series isn’t especially likely. It’s not about whether the status quo will or won’t be changed – it’s how cleverly the writers manage to keep it. And Sorry! pulls a trick that I doubt anyone would manage to predict, right at the very climax of the episode.

If you happen to have the episode to hand, I advise you sit down and give it a watch. For those that don’t, here’s the exact sequence of events:

- Early morning, and Muriel and Timothy leave the house to catch their train.

- They get out the front door… and Mother calls.

- Timothy goes back up the stairs, and gives his mother her medicine.

- He then goes back down the stairs, is about to leave with Muriel… and Mother calls again.

- Timothy goes back up the stairs. He forgot the spoon, the daft bastard.

- He tries to go back down, trips over Father, and falls down the stairs.

- From this point on, things get increasingly strange: a taxi magically appears, driven by his friend Frank; Mother and Father race after them in the car (“You want her to chase after you”, says Muriel. “That’s why you woke her up…”); the train station is staffed by Victor, one of Timothy’s librarian colleagues; the train pulls away, in a scene which looks like a movie…

…and Timothy wakes up in bed. Where all is revealed:

TIMOTHY: Where am I? Where am I?

MOTHER: In your own little bed.

TIMOTHY: What?

MOTHER: Yes. You slipped on the stairs. You fell right down and broke your crown. Now you stay here. I’m looking after you.

In other words: everything we see after Timothy falls down the stairs is a dream. With some programmes, maybe you’d be expecting some kind of twist like this; sometimes it almost feels a surprise when Star Trek goes a bit odd and then it doesn’t turn out to be some kind of hallucination. In a mainstream BBC family sitcom in 1982, however, I can’t imagine anyone would have figured out what was going on before the revelation – they may have figured out at some point that this was a dream, but they wouldn’t have figured out exactly when or how it started. People would have taken the fall down the stairs as just another bit of comic business.

Future episodes see more traditional dream sequences; “Perchance to Dream” in Series 2 is stuffed with meaningful dreams involving Timothy at school, and “The Big Sleep” which ends the third series5 involves an elaborate daydream involving a full military funeral, a mysterious lover in black, and a huge tombstone statue of Timothy himself. But this one is my favourite – not only for its unpredictability, but in its sheer construction. It’s not just something pulled out of a hat to provide some kind of shocking twist – it makes sense. The clues are there in plain view, yet there’s no chance you’ll work it out before you’re told. Much like that “inappropriate” title sequence, genre expectations point you off in entirely the wrong direction.

And that is the story of how Ian Davidson and Peter Vincent wrote one of my favourite dream sequences of all time.

Whilst the oft-quoted “only six episodes a year” for British sitcoms is overstated – check out Keeping Up Appearances or Drop the Dead Donkey – seventeen episodes was still pretty unusual. ↩

Excluding Get Fit With Brittas – an strange little 6×10 minute series with Brittas advocating how to live a healthy lifestyle. ↩

Let’s forget about the bizarre final episode of Series 4, “Collapse of a Small Party”, where Timothy gets mixed up in saving a circus from bailiffs. For some reason. ↩

I will try to keep my lusting after Marguerite Hardiman to a bare minimum. ↩

Noticing a pattern here? ↩

2 comments

Michelle on 25 September 2014 @ 8pm

My main problem with how ‘TCotTW’ ends is the fact it Hetro-norms Tim and Gavin. They really were just a sweet couple who’s sexuality is barely touched upon which arguably makes them two of the most positive just-happen-to-be-gay characters on television, then and now. Also it presents the logic flaw of, if Gordon didn’t know about them, why would he “Dream” them that way? Nice piece :)

chris on 28 September 2014 @ 5pm

Thanks for this article – I couldn’t help but be reminded of the legendary finale of Newhart, which did the exact same thing but in a way that the audience absolutely loved.

Comments on this post are now closed.